This Halloween five of the young people who call me “Grandpa” attended their Catholic school dressed as saints. The eight-year-old twins made themselves over into Saint Benedict and Saint Margaret of Scotland; the six-year-olds were Joan of Arc and Ignatius Loyola (first graders apparently like saints who carried swords); the kindergartener put on a miniature cassock and became Padre Pio. They wore these same costumes for their evening trick-or-treating, which drew baffled looks from the some of the homeowners they visited.

The next day was November 1, All Saints, a holy day of obligation when Catholics are supposed to attend Mass. The 8:30 a.m. Mass was jammed, mostly with other large families, and we had to stand in the vestibule of the church. During the service the behavior of my grandchildren astonished me. With the exception of the toddlers, the other children behaved reverently, though they could see nothing of the Mass and the audio system was on the fritz. Clearly, my daughter and her husband have taught these children the importance of the Eucharist.

On the drive home—I was alone in my car—I listened for a brief time to the local Catholic radio station. A Catholic evangelist, Steven Ray, was telling the host of the show that he encouraged the parents of his own grandchildren to raise their sons and daughters to be martyrs for the Faith. One of the grandchildren who had overheard Ray asked, “Do you want us to be dead, Grandpa?” No, he explained to her, he wanted her to grow up holy, to live, and if necessary, to die for her Catholic beliefs.

My time at Mass, my observations of my grandchildren, and Mr. Ray’s remarks gave rise to several thoughts.

Many Americans, I think, misunderstand martyrdom. We are well aware of Islamist terrorists who, having blown up themselves and innocent people, are declared martyrs by certain imams and other religious leaders.

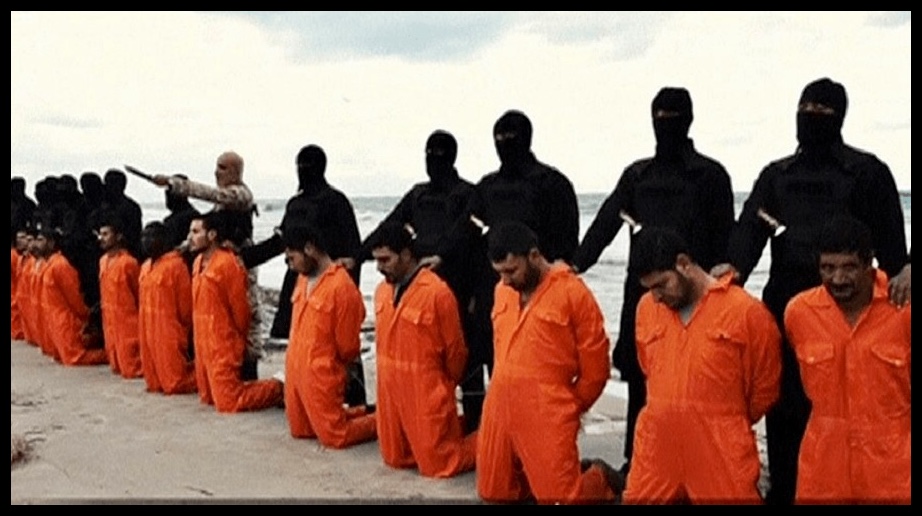

But this martyrdom by death differs radically from that espoused by Christians today. For Christians, Protestant or Catholic, martyrdom by physical death, known also as “red martyrs,” occurs when men, women, and children are executed for their belief in Christ. They are not jihadists who take the lives of others. No—they are those souls who refuse to recant their beliefs, preferring instead to die with the hope of entering heaven and finding union with God.

In recent times, this killing of Christians has worsened. In 2013, some 2,100 Christians worldwide were singled out and killed for their beliefs, most of them by Islamist terrorists. In 2015, that number rose to over 7,100 men, women, and children executed or assassinated for standing by their Faith. These figures do not include the tens of thousands who died as casualties in various wars on Christianity.

Occasionally I have heard someone, usually a young person, say: “Nothing’s worth dying for.” This is an opinion with which I profoundly disagreed. I adhere to the opposite adage: “If nothing is worth dying for, nothing is worth living for.”

So what about me? For what or for whom would I be willing to lay down my life?

Like most parents, I am certain I would give up my life for one of my children or grandchildren. That sacrifice is axiomatic. It goes with the job and is beyond debate.

In an emergency situation—a gunman opens fire in a restaurant, a baby is trapped in a burning car—I might conceivably risk death and intervene, but I’d be running on adrenalin and a sense of pride rather than principle.

Solders fight and die for their country, often in places most people back home can’t find on a map. Theirs is a worthy sacrifice whatever the cause, because they serve at the behest of our nation. When I was eighteen, the idea of dying for my country seemed right and just to me. Much older now, I look at my country and hardly recognize it anymore. Were I to become a soldier with my present attitude, I suspect I would do so for adventure, camaraderie, and financial benefits rather than for love of my government. Country yes, government no.

But what about faith? Would I die for Christ?

Many Christians I know, Protestant and Catholic, would answer that question with a resounding “Yes!” And sitting here at my desk, tea at my elbow, comfortable and well-fed, my answer would also be “Yes.”

But allow me to create a scenario based vaguely on an incident in the Middle East this past year. Suppose Islamist fanatics round up you and eleven of your friends, tie your hands behind your back, and march you to the beach. There they shove you to your knees on the sand. You are kneeling at one end of the line. An executioner draws his sword, raises it, and lops off the head of the man at the other end of the line. You can see the head as it rolls a few feet toward the sea, spouting blood, the face horribly twisted with pain. There is another shout of “Allahu Akbar!” and another head rolls in the bright, hot sand. The man kneeling and praying next to you defecates from fear. You look out at the sea you have loved all your life and you are praying “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, a sinner,” and your nostrils are filled with the stink of death and horror.

And then it’s your turn.

Would you die for your faith? Or would you cry out for mercy?

Can any of us answer that first question with absolute assurance?

I know I can’t. Not with absolute assurance.

Nevertheless, I hope I would receive the grace to die for my faith. I also hope I would have the grace to ask God to forgive the man with the blade and the grit to tell the bastard to swing away.

Next time: Grace and Grit: Part II: Gray Martyrdom

On the drive home—I was alone in my car—I listened for a brief time to the local Catholic radio station. A Catholic evangelist, Steven Ray, was telling the host of the show that he encouraged the parents of his own grandchildren to raise their sons and daughters to be martyrs for the Faith. One of the grandchildren who had overheard Ray asked, “Do you want us to be dead, Grandpa?” No, he explained to her, he wanted her to grow up holy, to live, and if necessary, to die for her Catholic beliefs.

My time at Mass, my observations of my grandchildren, and Mr. Ray’s remarks gave rise to several thoughts.

Many Americans, I think, misunderstand martyrdom. We are well aware of Islamist terrorists who, having blown up themselves and innocent people, are declared martyrs by certain imams and other religious leaders.

But this martyrdom by death differs radically from that espoused by Christians today. For Christians, Protestant or Catholic, martyrdom by physical death, known also as “red martyrs,” occurs when men, women, and children are executed for their belief in Christ. They are not jihadists who take the lives of others. No—they are those souls who refuse to recant their beliefs, preferring instead to die with the hope of entering heaven and finding union with God.

In recent times, this killing of Christians has worsened. In 2013, some 2,100 Christians worldwide were singled out and killed for their beliefs, most of them by Islamist terrorists. In 2015, that number rose to over 7,100 men, women, and children executed or assassinated for standing by their Faith. These figures do not include the tens of thousands who died as casualties in various wars on Christianity.

Occasionally I have heard someone, usually a young person, say: “Nothing’s worth dying for.” This is an opinion with which I profoundly disagreed. I adhere to the opposite adage: “If nothing is worth dying for, nothing is worth living for.”

So what about me? For what or for whom would I be willing to lay down my life?

Like most parents, I am certain I would give up my life for one of my children or grandchildren. That sacrifice is axiomatic. It goes with the job and is beyond debate.

In an emergency situation—a gunman opens fire in a restaurant, a baby is trapped in a burning car—I might conceivably risk death and intervene, but I’d be running on adrenalin and a sense of pride rather than principle.

Solders fight and die for their country, often in places most people back home can’t find on a map. Theirs is a worthy sacrifice whatever the cause, because they serve at the behest of our nation. When I was eighteen, the idea of dying for my country seemed right and just to me. Much older now, I look at my country and hardly recognize it anymore. Were I to become a soldier with my present attitude, I suspect I would do so for adventure, camaraderie, and financial benefits rather than for love of my government. Country yes, government no.

But what about faith? Would I die for Christ?

Many Christians I know, Protestant and Catholic, would answer that question with a resounding “Yes!” And sitting here at my desk, tea at my elbow, comfortable and well-fed, my answer would also be “Yes.”

But allow me to create a scenario based vaguely on an incident in the Middle East this past year. Suppose Islamist fanatics round up you and eleven of your friends, tie your hands behind your back, and march you to the beach. There they shove you to your knees on the sand. You are kneeling at one end of the line. An executioner draws his sword, raises it, and lops off the head of the man at the other end of the line. You can see the head as it rolls a few feet toward the sea, spouting blood, the face horribly twisted with pain. There is another shout of “Allahu Akbar!” and another head rolls in the bright, hot sand. The man kneeling and praying next to you defecates from fear. You look out at the sea you have loved all your life and you are praying “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, a sinner,” and your nostrils are filled with the stink of death and horror.

And then it’s your turn.

Would you die for your faith? Or would you cry out for mercy?

Can any of us answer that first question with absolute assurance?

I know I can’t. Not with absolute assurance.

Nevertheless, I hope I would receive the grace to die for my faith. I also hope I would have the grace to ask God to forgive the man with the blade and the grit to tell the bastard to swing away.

Next time: Grace and Grit: Part II: Gray Martyrdom

RSS Feed

RSS Feed