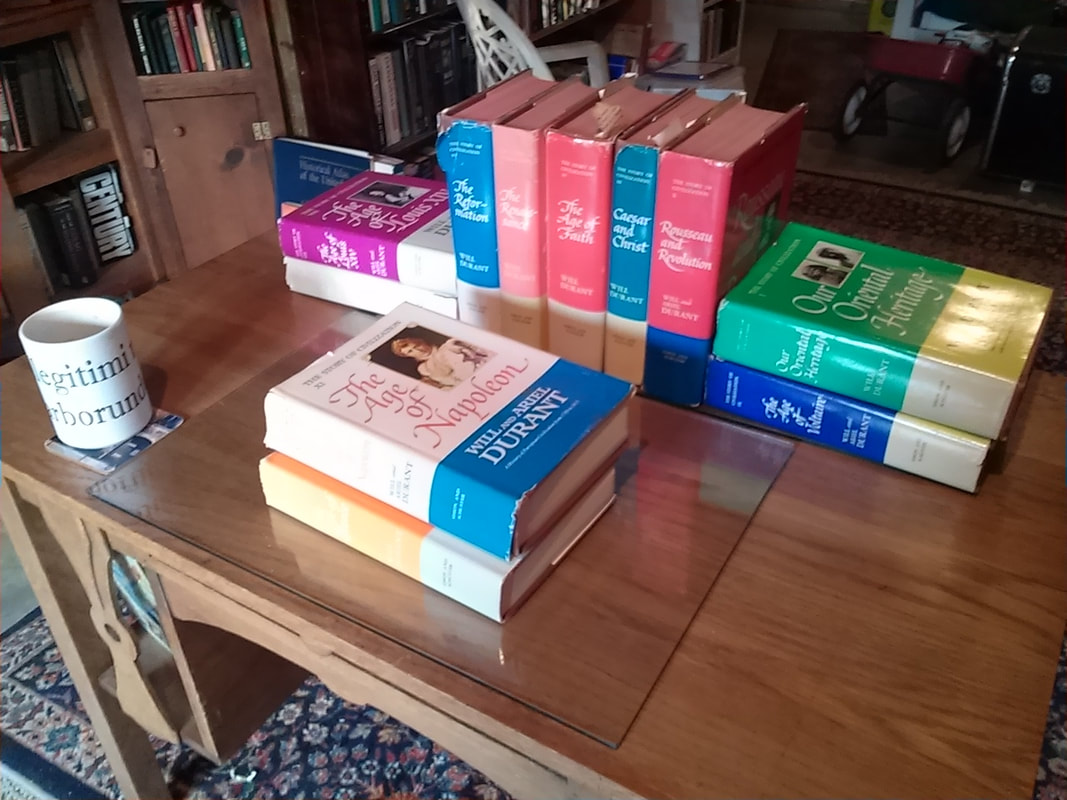

Brain Food: Reading The Story Of Civilization

“The Mohammedan Conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history.”

Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage, 459

“In 1916…twenty thousand Hindus met death from the fangs of snakes.”

Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage, 477

“King Porus is said to have selected, as a specially valuable gift for Alexander, not gold or silver, but thirty pounds of steel.”

Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage, 529

“Fools invent more hypotheses than philosophers ever refute, and philosophers often join them in the game.”

Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage, 545

“There is no humorist like history.”

Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage, 525

So I am well past page 500 of Durant’s Volume I, having driven through Indian philosophy and now tackling the section on literature.

My reading about the culture and history of the subcontinent brought me several realizations.

First, despite several courses in college that touched on the history and religion of India, I now comprehend the depths of my ignorance regarding India’s many contributions to civilization, particularly in science and medicine. That ignorance only increases the pleasure of my reading. (Since about the age of forty, I’ve openly acknowledged my ignorance about any number of things. Ask me about global warning, for instance, and I simply say I am too dumb to comment. In fact, pondering my ignorance right now, I realize that in many subjects, ranging from astrology to zoology, I am as dumb as a brick. One of my better points as a teacher was an ability to say, “I don’t know.” That truth remains. What I don’t know could fill the Library of Congress. What I do know could fit into three or four medium sized volumes. The good news is that one thing I know is that I don’t know much.)

Each page on India offers new information, and though I won’t retain the great bulk of this material, Durant has introduced me to a fascinating panorama of people, ideas, art, and culture. That writers in India used the bark of trees for their paper, that at various times enormous universities and thousands of schools made India one of the most literate of ancient cultures, that in the art of medicine skilled physicians like Sushruta were sophisticated enough to undertake primitive plastic surgery: these and scores of other details unknown to me make this book a feast.

Reading Durant has also made me aware of the repetitions in history and the staying power of social institutions. The Muslim invaders of India, for example, wrecked, burned, and destroyed Hindu temples, schools, libraries, and statues, behaving much as they do today in destroying non-Islamic shrines and monuments of the Middle East. I was aware that arranged marriages were still common in India—this system of matrimony actually breeds as much happiness and success, if not more, as in the West—but until I researched the topic a bit online, I had assumed that the caste system was extinct. Apparently, it still exists, particularly in the rural areas.

Finally, reading Durant provides exercise and power food for my mind. I read extensively and am paid to review books for the Smoky Mountain News, but much of that reading requires few mental gymnastics. The fiction is easily comprehended and plays more to feelings than to thought, and the biographies, histories, and social commentary deal with subjects with which I am already somewhat familiar.

Durant is different. His prose is lucid, generally clear, and easily absorbed, but to read him requires a different set of mental tools than the ones I normally pack on the truck. Take the following sentence:

“Just as there are two selves—the ego and Atman—and two worlds—the phenomenal and the noumenal—so there are two deities: an Ishvara or Creator worshiped by the people through the patterns of space, time and change; and a Brahman or Pure being worshiped by that philosophical piety which seeks and finds, behind all separate things and selves, one universal reality, unchanging amid all changes, indivisible among all divisions, eternal despite all vicissitudes of form, all birth and death.”

Such compression of ideas coupled with Durant’s wonderful sense of balance and rhythm within a sentence sparks the brain. (An admission: I resorted to a dictionary to understand “noumenal,” which has to do with the essence of an object rather than its perception by an outsider. After looking up the word, I thought to myself, Well, you’ll never see that one again. The very next day, I was passing the new fiction shelves at the public library and a title leaped out at me: Noumenon. I love when such coincidences happens.)

I mentioned ignorance earlier. One final thought on that subject comes from Gustave Flaubert: “Our ignorance of history makes us slander our own times.” The greatest rulers of India and Babylon, the wealthiest men and women of Assyria and China lived off the sweat and blood of thousands, yet lacked the amenities and riches we, even the poor among us, take for granted nowadays. We plop an ice cube into a drink without a thought as to that act being so rare in human history; we can visit any public library or go online, and find a world of knowledge at our fingertips; we are propelled through space by dented vehicles that would leave the Egyptian king’s swiftest chariot eating dust.

We bewail the vices and discomforts of our time, with little consideration of the rigors faced by our great-great grandparents, much less by the dusty workers dragooned into building a Taj Mahal or a Pyramid.

Here's to 2018!

Each page on India offers new information, and though I won’t retain the great bulk of this material, Durant has introduced me to a fascinating panorama of people, ideas, art, and culture. That writers in India used the bark of trees for their paper, that at various times enormous universities and thousands of schools made India one of the most literate of ancient cultures, that in the art of medicine skilled physicians like Sushruta were sophisticated enough to undertake primitive plastic surgery: these and scores of other details unknown to me make this book a feast.

Reading Durant has also made me aware of the repetitions in history and the staying power of social institutions. The Muslim invaders of India, for example, wrecked, burned, and destroyed Hindu temples, schools, libraries, and statues, behaving much as they do today in destroying non-Islamic shrines and monuments of the Middle East. I was aware that arranged marriages were still common in India—this system of matrimony actually breeds as much happiness and success, if not more, as in the West—but until I researched the topic a bit online, I had assumed that the caste system was extinct. Apparently, it still exists, particularly in the rural areas.

Finally, reading Durant provides exercise and power food for my mind. I read extensively and am paid to review books for the Smoky Mountain News, but much of that reading requires few mental gymnastics. The fiction is easily comprehended and plays more to feelings than to thought, and the biographies, histories, and social commentary deal with subjects with which I am already somewhat familiar.

Durant is different. His prose is lucid, generally clear, and easily absorbed, but to read him requires a different set of mental tools than the ones I normally pack on the truck. Take the following sentence:

“Just as there are two selves—the ego and Atman—and two worlds—the phenomenal and the noumenal—so there are two deities: an Ishvara or Creator worshiped by the people through the patterns of space, time and change; and a Brahman or Pure being worshiped by that philosophical piety which seeks and finds, behind all separate things and selves, one universal reality, unchanging amid all changes, indivisible among all divisions, eternal despite all vicissitudes of form, all birth and death.”

Such compression of ideas coupled with Durant’s wonderful sense of balance and rhythm within a sentence sparks the brain. (An admission: I resorted to a dictionary to understand “noumenal,” which has to do with the essence of an object rather than its perception by an outsider. After looking up the word, I thought to myself, Well, you’ll never see that one again. The very next day, I was passing the new fiction shelves at the public library and a title leaped out at me: Noumenon. I love when such coincidences happens.)

I mentioned ignorance earlier. One final thought on that subject comes from Gustave Flaubert: “Our ignorance of history makes us slander our own times.” The greatest rulers of India and Babylon, the wealthiest men and women of Assyria and China lived off the sweat and blood of thousands, yet lacked the amenities and riches we, even the poor among us, take for granted nowadays. We plop an ice cube into a drink without a thought as to that act being so rare in human history; we can visit any public library or go online, and find a world of knowledge at our fingertips; we are propelled through space by dented vehicles that would leave the Egyptian king’s swiftest chariot eating dust.

We bewail the vices and discomforts of our time, with little consideration of the rigors faced by our great-great grandparents, much less by the dusty workers dragooned into building a Taj Mahal or a Pyramid.

Here's to 2018!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed