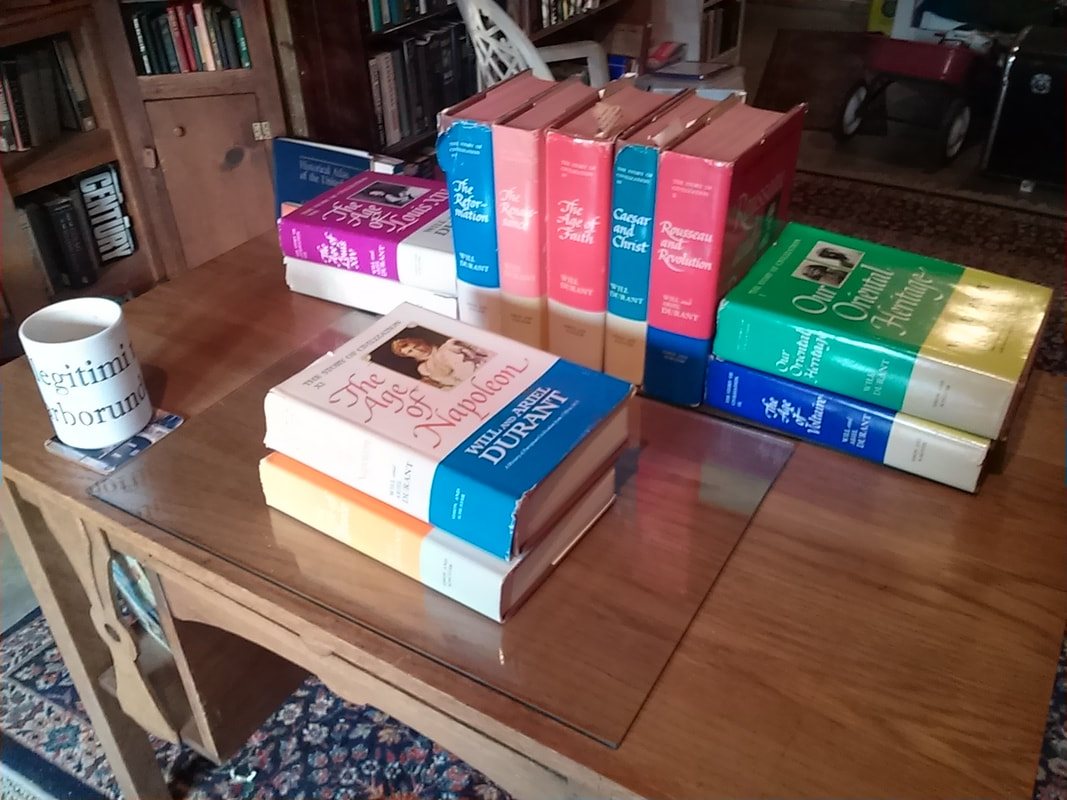

Whooo-hoooo.

Another volume of Durant is finished.

Long ago, when I was in graduate school at Wake Forest University, I wanted to write my master’s thesis on some aspect of the Crusades. My adviser, a fine man named Jim Barefield, steered me away from that topic and directed me to write on “The King’s Council During The Minority of Henry III of England.”

Sounded about as exciting as day old dishwater, right?

Another volume of Durant is finished.

Long ago, when I was in graduate school at Wake Forest University, I wanted to write my master’s thesis on some aspect of the Crusades. My adviser, a fine man named Jim Barefield, steered me away from that topic and directed me to write on “The King’s Council During The Minority of Henry III of England.”

Sounded about as exciting as day old dishwater, right?

But as I got into my topic, with all the politics of various advisers and the jockeying for position regarding William Marshall and the boy king, my interest blossomed, not only because of the subject, but because our country was undergoing the Watergate hearings at the same time. In those hearings, the voices of accusers and accused echoed down the centuries to the thirteenth century court of the English court. Here were the same behind the scenes meetings, the betrayals, the honor displayed by some of the barons and church prelates, and the greed and treachery shown by others.

I experienced this same feeling in the last two weeks of my reading of Durant’s The Age of Voltaire.

Eighteenth century France, and to a lesser extent England and Germany, reflect our present turmoil, even down to the causes and individuals, particularly in regard to the Brett Kavanaugh ordeal. The Age of Voltaire pitted philosophes against the Church and anti-philosophes; our present age pits progressives against conservatives. The principle ideas have swung 180 degrees: the philosophes claimed to be arguing from reason, their opponents from faith and feeling; today the progressives play on emotions while the conservatives look for their guide to reason. But the passions on both sides in both centuries, and many of the same ideas, from the nature of human beings to the best political systems, from the rule of the elites to the best educational system, remain the bonfires today as they were then.

And as usual, the Durants impressed me with their asides and witticisms. Here are a few:

From Elie Freron, an anti-philosophe: “You talk of nothing but tolerance, and never was a sect more intolerant….”

From the Durants: “Heaven and utopia are the rival buckets that hover over the well of fate: when one goes down the other goes up; hope draws up one or the other in turn. Perhaps when both buckets come up empty a civilization loses heart and begins to die.” (A good number of Americans have ceased to believe in heaven. I suspect a good number have ceased to believe in Utopia as well. We will see what happens.)

At the end of the book the Durants add an imagined dialogue between Pope Benedict XIV and Voltaire. Here Benedict speaks: “Destroy an organized faith, and it will be replaced by that wilderness of disorderly superstitions that are now arising like maggots in the wounds of Christianity.”

Here’s a nugget to deeply contemplate. Again Benedict speaks: “There is nothing so shallow as sophistication: it judges everything from the surface and thinks it is profound.” Here, I think, is one of the worms eating at the heart of modern life.

“Define your terms!” The Durants describe these words as the famous Voltairean imperative. How many arguments, how many quarrels, how many misunderstandings might be avoided if we defined our terms before we shot out our opinions.

Regarding a frenzy of revenge in Toulouse, Durant writes: “The people of Toulouse thought en masse, as a crowd; and crowds can feel but they cannot think.” Apply this one where you like, given recent events.

On to Rousseau and Revolution.

I experienced this same feeling in the last two weeks of my reading of Durant’s The Age of Voltaire.

Eighteenth century France, and to a lesser extent England and Germany, reflect our present turmoil, even down to the causes and individuals, particularly in regard to the Brett Kavanaugh ordeal. The Age of Voltaire pitted philosophes against the Church and anti-philosophes; our present age pits progressives against conservatives. The principle ideas have swung 180 degrees: the philosophes claimed to be arguing from reason, their opponents from faith and feeling; today the progressives play on emotions while the conservatives look for their guide to reason. But the passions on both sides in both centuries, and many of the same ideas, from the nature of human beings to the best political systems, from the rule of the elites to the best educational system, remain the bonfires today as they were then.

And as usual, the Durants impressed me with their asides and witticisms. Here are a few:

From Elie Freron, an anti-philosophe: “You talk of nothing but tolerance, and never was a sect more intolerant….”

From the Durants: “Heaven and utopia are the rival buckets that hover over the well of fate: when one goes down the other goes up; hope draws up one or the other in turn. Perhaps when both buckets come up empty a civilization loses heart and begins to die.” (A good number of Americans have ceased to believe in heaven. I suspect a good number have ceased to believe in Utopia as well. We will see what happens.)

At the end of the book the Durants add an imagined dialogue between Pope Benedict XIV and Voltaire. Here Benedict speaks: “Destroy an organized faith, and it will be replaced by that wilderness of disorderly superstitions that are now arising like maggots in the wounds of Christianity.”

Here’s a nugget to deeply contemplate. Again Benedict speaks: “There is nothing so shallow as sophistication: it judges everything from the surface and thinks it is profound.” Here, I think, is one of the worms eating at the heart of modern life.

“Define your terms!” The Durants describe these words as the famous Voltairean imperative. How many arguments, how many quarrels, how many misunderstandings might be avoided if we defined our terms before we shot out our opinions.

Regarding a frenzy of revenge in Toulouse, Durant writes: “The people of Toulouse thought en masse, as a crowd; and crowds can feel but they cannot think.” Apply this one where you like, given recent events.

On to Rousseau and Revolution.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed