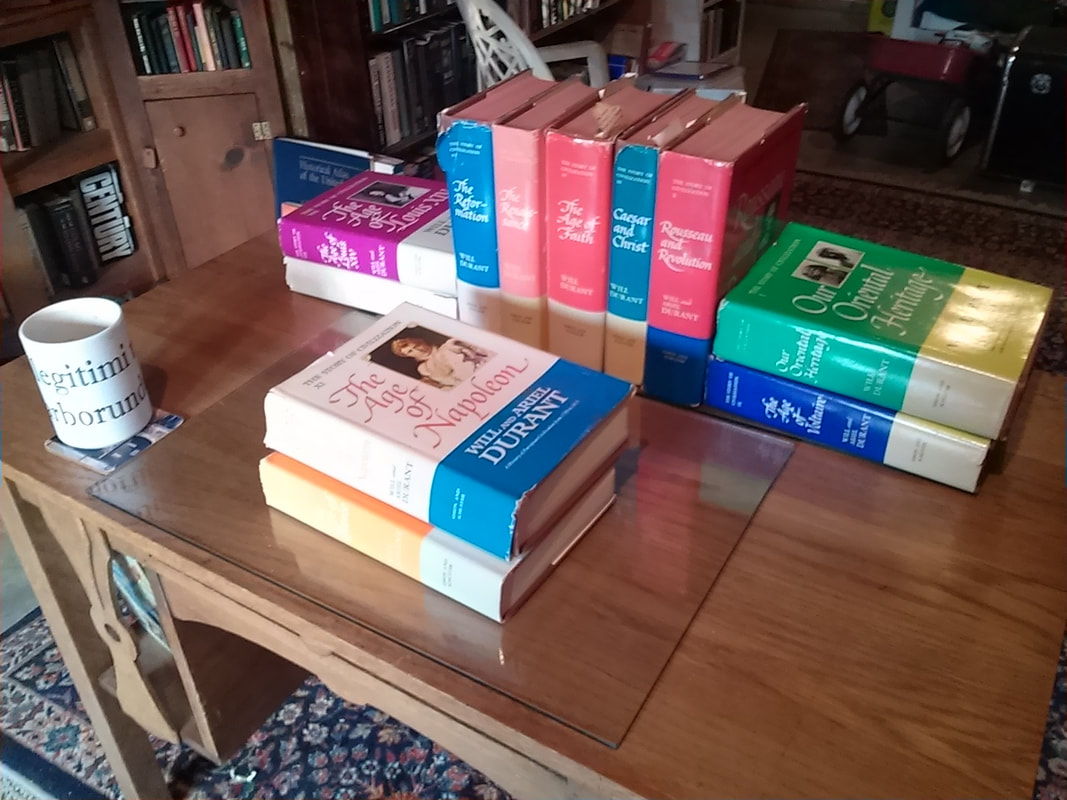

Six days ago, I finished Volume X, Rousseau and Revolution, in The Story of Civilization, and am now up to page 250 in the last volume, The Age of Napoleon, of Will and Ariel Durant’s magnum opus. I shall, Deo volente, finish my self-appointed project of reading this set before the end of the year.

Right now the Durants are instructing me on life during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic years. As I am reading, I am struck again and again, as has happened so often in my march through these pages, by the resemblance between our ancestors and ourselves. Oh, we have grown a little more sophisticated. We no longer hoist the head of our enemy on a pike and parade it through the streets, though given today’s ugly politics some may wish to do so. By and large, however, we have much more in common with those who came before us than we may realize. Here, for example, are a few observations by the Durants on the Revolution:

As usual the leading actors were more famous than the statesmen….

Between 1789 and 1839, twenty-four percent of all brides in the typical town of Meulan were pregnant when they came to the altar.

Paternal authority was lessened by the moderate growth of women’s legal rights, and still more by the assertion of emancipated youth.

Pornographic literature abounded….

In the lower classes there were many cases of a couple living together unwed and unmolested.

(Children born out of wedlock) were plentiful; in 1796 France recorded 44,000 foundlings.

Even during the violent period between the September Massacres of 1792 and the fall of Robespierre in July 1794, when there were 2,800 executions in Paris, life for nearly all the survivors went its customary round of work and play, of sexual pursuit and parental love.

Here…was one of the most difficult enterprises of the Revolution, as it is one of the difficult problems of our time: to build a social order upon a system of morality independent of religious belief.

Any of these statements might apply to our own time. More Americans, for example, are more like to recognize the names Kim Kardashian or Matt Damon than Vice-President Mike Pence. Like the French of that day, we have recorded in the last forty years a huge increase in births to single mothers. And so on and so on….

Since the French Revolution, science and technology have, of course, leaped eons ahead of a society that lighted the darkness with candles and traveled rutted roads in rough horse-drawn wagons. Literally at our fingertips we have gadgets that Danton, De Stael, and David could scarcely imagine. Compared to our predecessors, even in regard to our grandparents, in terms of comfort, safety, and health the twenty-first century for the great mass of humanity is a veritable paradise.

Yet the heart and mind—and soul, for those of you who believe—are little changed. Just like the people of the eighteenth century, or for that matter, human beings in nearly every historical era and place, we love and we hate, we comfort or mock, we applaud or envy, we trust or doubt, we argue about what constitutes good and evil. Most of the time, just like pre-modern people, we have little understanding of our own motivations, much less those of our friends and enemies.

For better and for worse our human nature remains largely unaltered.

Some may find that idea sad or disturbing. They wish human beings might move away from their proclivities for evil: violence, hatred, racism, sheer junkyard dog meanness. Some work for change through their political beliefs, passing laws intended to improve human relationships, while others seek through their religious faith to battle evil in the human heart.

Others—and I include myself—may take a different, not an opposite, view. We are the ones who believe that change comes from within each heart, that neither the state nor the culture can effect large changes in human nature. We recognize the ugliness of the human race, but also its goodness. We remember the words of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: “Gradually it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either -- but right through every human heart -- and through all human hearts.”

Solzhenitsyn’s wise observation might apply to the citizens of Ancient Rome, to the men and women of the Reformation, to the farmers and laborers of Revolutionary France, and to the technicians and professors of our own day.

The way we were is the way we are.

As usual the leading actors were more famous than the statesmen….

Between 1789 and 1839, twenty-four percent of all brides in the typical town of Meulan were pregnant when they came to the altar.

Paternal authority was lessened by the moderate growth of women’s legal rights, and still more by the assertion of emancipated youth.

Pornographic literature abounded….

In the lower classes there were many cases of a couple living together unwed and unmolested.

(Children born out of wedlock) were plentiful; in 1796 France recorded 44,000 foundlings.

Even during the violent period between the September Massacres of 1792 and the fall of Robespierre in July 1794, when there were 2,800 executions in Paris, life for nearly all the survivors went its customary round of work and play, of sexual pursuit and parental love.

Here…was one of the most difficult enterprises of the Revolution, as it is one of the difficult problems of our time: to build a social order upon a system of morality independent of religious belief.

Any of these statements might apply to our own time. More Americans, for example, are more like to recognize the names Kim Kardashian or Matt Damon than Vice-President Mike Pence. Like the French of that day, we have recorded in the last forty years a huge increase in births to single mothers. And so on and so on….

Since the French Revolution, science and technology have, of course, leaped eons ahead of a society that lighted the darkness with candles and traveled rutted roads in rough horse-drawn wagons. Literally at our fingertips we have gadgets that Danton, De Stael, and David could scarcely imagine. Compared to our predecessors, even in regard to our grandparents, in terms of comfort, safety, and health the twenty-first century for the great mass of humanity is a veritable paradise.

Yet the heart and mind—and soul, for those of you who believe—are little changed. Just like the people of the eighteenth century, or for that matter, human beings in nearly every historical era and place, we love and we hate, we comfort or mock, we applaud or envy, we trust or doubt, we argue about what constitutes good and evil. Most of the time, just like pre-modern people, we have little understanding of our own motivations, much less those of our friends and enemies.

For better and for worse our human nature remains largely unaltered.

Some may find that idea sad or disturbing. They wish human beings might move away from their proclivities for evil: violence, hatred, racism, sheer junkyard dog meanness. Some work for change through their political beliefs, passing laws intended to improve human relationships, while others seek through their religious faith to battle evil in the human heart.

Others—and I include myself—may take a different, not an opposite, view. We are the ones who believe that change comes from within each heart, that neither the state nor the culture can effect large changes in human nature. We recognize the ugliness of the human race, but also its goodness. We remember the words of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: “Gradually it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either -- but right through every human heart -- and through all human hearts.”

Solzhenitsyn’s wise observation might apply to the citizens of Ancient Rome, to the men and women of the Reformation, to the farmers and laborers of Revolutionary France, and to the technicians and professors of our own day.

The way we were is the way we are.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed