Long ago, a friend once asked me why Jesus didn’t come to earth today instead of two millennia ago. “If he had come to the modern world,” the friend said, “he could have appeared on television and in the papers. He would have been instantly famous. Evangelizing would have been so much easier.”

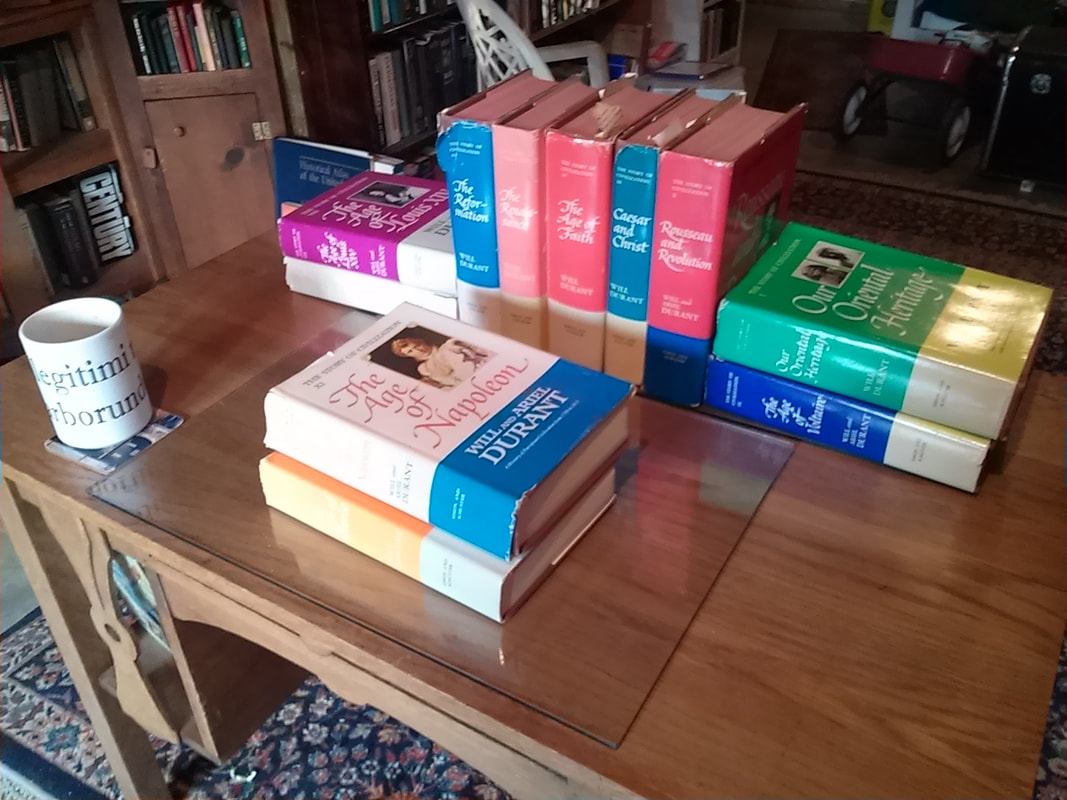

We’ll come back to that thought, but first let’s look at Will Durant’s Caesar and Christ.

We’ll come back to that thought, but first let’s look at Will Durant’s Caesar and Christ.

I am nearing the end of this thick volume on the history of Rome. Durant has taken me for quite a ride, escorting me through palaces and slums, guiding me hither and yon from one end of the Mediterranean to the other, allowing me to view battles, massacres, plagues, and other calamities from the safe heights of history.

Yesterday I was reading the chapter titled “The Hellenistic Revival,” which is set in the centuries when Rome has begun her final tottering fall into ruin. Here Durant describes cities such as Antioch and Ephesus, and various regions like North Africa and Asia Minor; he looks at the rise of mystery religions coming from the East and from North Africa; he tells us how a number of these religions involved gods who rise from the dead and worshippers who believe in an afterlife; he presents the Jewish philosopher Philo, who conceived of God as Logos, or the Word; he makes the point that Greek had become a common language throughout the Eastern Empire.

Durant ends the chapter with these words: “All the world seemed conspiring to prepare the way of Christ.”

It would be hard, I think, for any reader to absorb this chapter and then disagree with Durant’s conclusion. The cities to which Paul and the other apostles would evangelize were not shabby, squalid towns, but thriving centers of commerce and culture. Antioch, for example, then the capital of Syria, “had a system of street lighting that made it safe and brilliant at night,” with a main avenue over four miles long, paved with granite and boasting a covered colonnade on either side. “During the feast of Brumalia, lasting through most of December, the whole city, says a contemporary, resembled a tavern, and the streets rang all night with song and revelry.”

Those cities, the routes that connected them, the language common to so many people, the yearning in the hearts of many for a god of love, the Pax Romana: all these did indeed conspire to help spread the Christian message.

And as for Jesus coming today instead? In that time, Jesus Christ faced death on a cross, a common form of execution, and according to believers of that time and now, then rose from the dead, promised his followers an eternity with God, and urged them to carry His message to the ends of the earth.

Had He come today, particularly in this new millennium, I have little doubt that He would have died not by physical execution, but would instead have suffered the death of a thousand cuts of derision on all our electronic instruments. Now, as then, our skeptics and our “leaders” would tear him apart with mockery and malign attacks.

That whole issue is of little moment anyway. In the hearts of believers, He is always here.

Yesterday I was reading the chapter titled “The Hellenistic Revival,” which is set in the centuries when Rome has begun her final tottering fall into ruin. Here Durant describes cities such as Antioch and Ephesus, and various regions like North Africa and Asia Minor; he looks at the rise of mystery religions coming from the East and from North Africa; he tells us how a number of these religions involved gods who rise from the dead and worshippers who believe in an afterlife; he presents the Jewish philosopher Philo, who conceived of God as Logos, or the Word; he makes the point that Greek had become a common language throughout the Eastern Empire.

Durant ends the chapter with these words: “All the world seemed conspiring to prepare the way of Christ.”

It would be hard, I think, for any reader to absorb this chapter and then disagree with Durant’s conclusion. The cities to which Paul and the other apostles would evangelize were not shabby, squalid towns, but thriving centers of commerce and culture. Antioch, for example, then the capital of Syria, “had a system of street lighting that made it safe and brilliant at night,” with a main avenue over four miles long, paved with granite and boasting a covered colonnade on either side. “During the feast of Brumalia, lasting through most of December, the whole city, says a contemporary, resembled a tavern, and the streets rang all night with song and revelry.”

Those cities, the routes that connected them, the language common to so many people, the yearning in the hearts of many for a god of love, the Pax Romana: all these did indeed conspire to help spread the Christian message.

And as for Jesus coming today instead? In that time, Jesus Christ faced death on a cross, a common form of execution, and according to believers of that time and now, then rose from the dead, promised his followers an eternity with God, and urged them to carry His message to the ends of the earth.

Had He come today, particularly in this new millennium, I have little doubt that He would have died not by physical execution, but would instead have suffered the death of a thousand cuts of derision on all our electronic instruments. Now, as then, our skeptics and our “leaders” would tear him apart with mockery and malign attacks.

That whole issue is of little moment anyway. In the hearts of believers, He is always here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed