The article below appeared at The Epoch Times on March 26: https://www.theepochtimes.com/glimpses-of-heaven-icons-paintings-prayer-and-meditation_3278704.html

In the spring, just before my homeschooling seminars closed for the summer, my Latin students and I would head to the Basilica of Saint Lawrence in Asheville, North Carolina. We would gather in the courtyard outside the church, and I would issue my usual admonitions: whisper, don’t disturb those praying in the side chapel, walk, don’t run, and be respectful.

I then divided the students into teams, equipped each team with a Latin dictionary, and turned them loose inside the Basilica, where they engaged in a scavenger hunt, copying down the Latin inscriptions they found there and then translating them. I roamed from team to team, giving a hand with the translations or pointing them to a site they had missed. Most were a little shocked when I pulled open a heavy metal door in the wall, showed them the tomb of Rafael Guastavino, the architect who had designed the Basilica and donated money for its construction, and had them translate the Latin on the coffin.

Some of my students were Roman Catholics, and some were unaffiliated with any religion, but the great majority were devout Protestants, many of them members of the traditional Presbyterian Church in America. On first entering that sanctuary with its statues and paintings, its bank of votive candles, and the handful of people kneeling in prayer in Eucharistic adoration, my Protestant students inevitably paused while they absorbed these strange sights.

In the spring, just before my homeschooling seminars closed for the summer, my Latin students and I would head to the Basilica of Saint Lawrence in Asheville, North Carolina. We would gather in the courtyard outside the church, and I would issue my usual admonitions: whisper, don’t disturb those praying in the side chapel, walk, don’t run, and be respectful.

I then divided the students into teams, equipped each team with a Latin dictionary, and turned them loose inside the Basilica, where they engaged in a scavenger hunt, copying down the Latin inscriptions they found there and then translating them. I roamed from team to team, giving a hand with the translations or pointing them to a site they had missed. Most were a little shocked when I pulled open a heavy metal door in the wall, showed them the tomb of Rafael Guastavino, the architect who had designed the Basilica and donated money for its construction, and had them translate the Latin on the coffin.

Some of my students were Roman Catholics, and some were unaffiliated with any religion, but the great majority were devout Protestants, many of them members of the traditional Presbyterian Church in America. On first entering that sanctuary with its statues and paintings, its bank of votive candles, and the handful of people kneeling in prayer in Eucharistic adoration, my Protestant students inevitably paused while they absorbed these strange sights.

Art and Religion: Different Interpretations

Later, they would pepper me with questions: “Why were all those candles lit?” “Do Catholics worship statues?” “Why are there so many pictures of Mary?” “Tell me again why that guy is buried in the church?”

Religious statuary and paintings have in the past roused conflicts among Christians. In the 8th and 9th centuries, citing the injunction in the Ten Commandments against the worship of “graven images,” and after Emperor Leo III began banning icons, Byzantine iconoclasts (image breakers) declared war on paintings with human images inside churches, and destroyed many works of art. Occasionally, this fierce battle over icons led to bloodshed.

During the Reformation, Protestants practiced a similar iconoclasm, stripping churches of their statues, burning paintings, destroying altars, and smashing stained-glass windows. The cross replaced the crucifix, white plaster erased various mosaics.

Even today, some take sides in this ancient war. After coming back from Europe, where he had visited a number of churches, a friend told me he could never belong to a church where the devout kissed their fingers and touched them to a painting, or knelt before a statue of Mary. And certainly it’s tempting to regard that gesture, or kneeling in prayer before a statue, as idol worship.

Russian Icons

Yet those who engage in these practices are not worshipping the art itself, but what it represents. The Russian Orthodox, for example, have long regarded icons as sacred objects not because of paint and brush, but because these pictures open a window into heaven.

In “How to read and comprehend a Russian icon,” writer Irina Osipova and designer Ekaterina Chipurenko provide a splendid introduction to the art of the icon. Every detail on these wooden panels—color, perspective, dress, the most insignificant image— serves a purpose and has meaning. Osipova tells us, for example, that the color gray is never used in an icon, as it is a mixture of white and black, symbolic of good and evil. The eyes, the windows to the soul, are deliberately enlarged. We Westerners find icons stilted and strange in part because their artists use reverse perspective, “a drawing with vanishing points that are placed outside the painting,” creating an “illusion that these points are ‘in front of’ the painting”” and so focusing the viewer’s attention on the religious figures depicted.

Western European Religious Art

Like their Russian counterparts, for over a thousand years Western European painters largely devoted themselves to religious themes, producing paintings, statuary, glass, and even volumes of literature like the Book of Kells, psalters, and Bibles, all as objects whose beauty reflected what they took to be the glory of God. Some of us might consider these artists obsessed by religion, but that was not the case. No—they lived in a culture we can barely imagine today, an age when faith encompassed all of life, commanding morals, setting out the calendar of feast days, and formalizing cultural rituals ranging from coronations to baptisms, marriages, and funerals.

This art also served to educate a pre-literate people in Biblical tales and the life of Christ. Giotto’s “The Kiss of Judas,” Gentile Da Fabriano’s “The Adoration of the Magi,” the Master of the Rohan Hours “The Dead Man Before His Judge,” Jan van Eyck’s “Annunciation,” Rogier van der Weyden’s “Deposition”: here were visual stories for king and commoner alike, lessons and carols in paint rather than in music and words.

In the last five hundred years, the secularization of culture diminished this passion for sacred art. We still see some moderns producing religious works—St. John the Baptist Catholic Church in Front Royal, Virginia, for instance, boosts four paintings by Henry Wingate depicting scenes from John’s life—but for the most part representational artists now turn to landscapes, portraiture, and other subjects rather than exploring religious topics.

A Pathway to Prayer

Yet like their ancestors, some believers still look to art as inspiration for prayer, a gateway into the beyond. If we sat for a while in the pews of the Basilica, we would see parishioners and pilgrims enter the sanctuary, kneel before the statue of Mary or the reproduction of Poland’s “Black Madonna, say their prayers, and quietly leave the building.

This is not just a Roman Catholic phenomenon. In “Artful Contemplation: Praying with art during Lent and Easter,” Karen Sue Smith reports that a friend visiting a state museum in Moscow observed people kneeling on the floor of the museum in front of various icons, and sometimes leaving behind a flower or a candle. Whether in a church or a museum, an icon in Russia apparently remains a vehicle for prayer.

Closer to home, several people I know maintain small shrines in their living quarters, a space specially set aside for prayer. On a table or desk stands a reproduction of some religious art—a scene from the Bible, a portrait of the Virgin Mary—surrounded by candles, smaller paintings, prayer cards and books. Kneeling on the floor or on a prie-dieu, these believers offer up their morning and evening devotions.

The Power of Sacred Art

Christians of any denomination can use great art as a focal point for wayward minds and wandering eyes. As believers sink deeper into a painting, they find their thoughts turning to the sublime, the sacred, the eternal verities beyond their ken, which is, after all, the purpose of great art and of prayer.

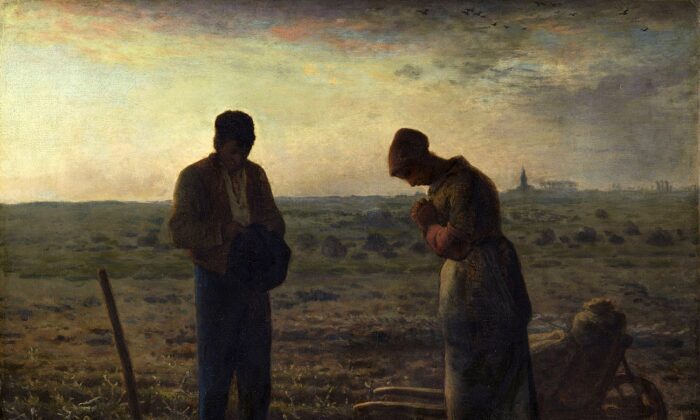

Let me end with a personal example of this power of art. This month found me sitting in a chair in the office of Dr. Hsu, an Ear, Noise, and Throat specialist here in town and a man of excellent reputation. Because I had a growth in my throat—the growth turned out to be real, but harmless—I was nervous. Across the room from me was a handsomely framed reproduction of Millet’s “The Angelus.” While awaiting the doctor’s arrival, I studied that lovely piece: the soft colors, a man and a woman standing in a field, heads bowed in prayer during the Angelus. As my eyes absorbed that painting, a calm came over me. Did I pray? Not consciously.

But I did find peace.

Later, they would pepper me with questions: “Why were all those candles lit?” “Do Catholics worship statues?” “Why are there so many pictures of Mary?” “Tell me again why that guy is buried in the church?”

Religious statuary and paintings have in the past roused conflicts among Christians. In the 8th and 9th centuries, citing the injunction in the Ten Commandments against the worship of “graven images,” and after Emperor Leo III began banning icons, Byzantine iconoclasts (image breakers) declared war on paintings with human images inside churches, and destroyed many works of art. Occasionally, this fierce battle over icons led to bloodshed.

During the Reformation, Protestants practiced a similar iconoclasm, stripping churches of their statues, burning paintings, destroying altars, and smashing stained-glass windows. The cross replaced the crucifix, white plaster erased various mosaics.

Even today, some take sides in this ancient war. After coming back from Europe, where he had visited a number of churches, a friend told me he could never belong to a church where the devout kissed their fingers and touched them to a painting, or knelt before a statue of Mary. And certainly it’s tempting to regard that gesture, or kneeling in prayer before a statue, as idol worship.

Russian Icons

Yet those who engage in these practices are not worshipping the art itself, but what it represents. The Russian Orthodox, for example, have long regarded icons as sacred objects not because of paint and brush, but because these pictures open a window into heaven.

In “How to read and comprehend a Russian icon,” writer Irina Osipova and designer Ekaterina Chipurenko provide a splendid introduction to the art of the icon. Every detail on these wooden panels—color, perspective, dress, the most insignificant image— serves a purpose and has meaning. Osipova tells us, for example, that the color gray is never used in an icon, as it is a mixture of white and black, symbolic of good and evil. The eyes, the windows to the soul, are deliberately enlarged. We Westerners find icons stilted and strange in part because their artists use reverse perspective, “a drawing with vanishing points that are placed outside the painting,” creating an “illusion that these points are ‘in front of’ the painting”” and so focusing the viewer’s attention on the religious figures depicted.

Western European Religious Art

Like their Russian counterparts, for over a thousand years Western European painters largely devoted themselves to religious themes, producing paintings, statuary, glass, and even volumes of literature like the Book of Kells, psalters, and Bibles, all as objects whose beauty reflected what they took to be the glory of God. Some of us might consider these artists obsessed by religion, but that was not the case. No—they lived in a culture we can barely imagine today, an age when faith encompassed all of life, commanding morals, setting out the calendar of feast days, and formalizing cultural rituals ranging from coronations to baptisms, marriages, and funerals.

This art also served to educate a pre-literate people in Biblical tales and the life of Christ. Giotto’s “The Kiss of Judas,” Gentile Da Fabriano’s “The Adoration of the Magi,” the Master of the Rohan Hours “The Dead Man Before His Judge,” Jan van Eyck’s “Annunciation,” Rogier van der Weyden’s “Deposition”: here were visual stories for king and commoner alike, lessons and carols in paint rather than in music and words.

In the last five hundred years, the secularization of culture diminished this passion for sacred art. We still see some moderns producing religious works—St. John the Baptist Catholic Church in Front Royal, Virginia, for instance, boosts four paintings by Henry Wingate depicting scenes from John’s life—but for the most part representational artists now turn to landscapes, portraiture, and other subjects rather than exploring religious topics.

A Pathway to Prayer

Yet like their ancestors, some believers still look to art as inspiration for prayer, a gateway into the beyond. If we sat for a while in the pews of the Basilica, we would see parishioners and pilgrims enter the sanctuary, kneel before the statue of Mary or the reproduction of Poland’s “Black Madonna, say their prayers, and quietly leave the building.

This is not just a Roman Catholic phenomenon. In “Artful Contemplation: Praying with art during Lent and Easter,” Karen Sue Smith reports that a friend visiting a state museum in Moscow observed people kneeling on the floor of the museum in front of various icons, and sometimes leaving behind a flower or a candle. Whether in a church or a museum, an icon in Russia apparently remains a vehicle for prayer.

Closer to home, several people I know maintain small shrines in their living quarters, a space specially set aside for prayer. On a table or desk stands a reproduction of some religious art—a scene from the Bible, a portrait of the Virgin Mary—surrounded by candles, smaller paintings, prayer cards and books. Kneeling on the floor or on a prie-dieu, these believers offer up their morning and evening devotions.

The Power of Sacred Art

Christians of any denomination can use great art as a focal point for wayward minds and wandering eyes. As believers sink deeper into a painting, they find their thoughts turning to the sublime, the sacred, the eternal verities beyond their ken, which is, after all, the purpose of great art and of prayer.

Let me end with a personal example of this power of art. This month found me sitting in a chair in the office of Dr. Hsu, an Ear, Noise, and Throat specialist here in town and a man of excellent reputation. Because I had a growth in my throat—the growth turned out to be real, but harmless—I was nervous. Across the room from me was a handsomely framed reproduction of Millet’s “The Angelus.” While awaiting the doctor’s arrival, I studied that lovely piece: the soft colors, a man and a woman standing in a field, heads bowed in prayer during the Angelus. As my eyes absorbed that painting, a calm came over me. Did I pray? Not consciously.

But I did find peace.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed