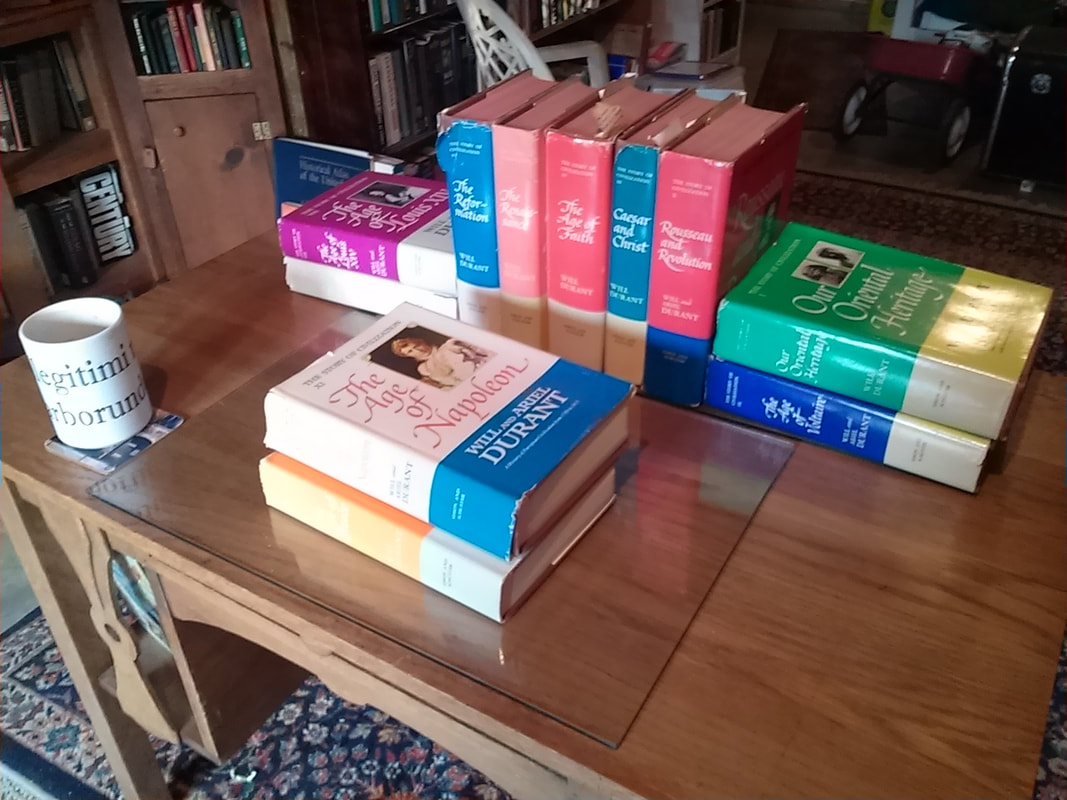

Having read about halfway through Will Durant’s The Life of Greece, Volume II of The Story of Civilization, I keep coming across all sorts of observations about the Greeks that could just as easily apply to our own time. Plus ca meme, plus c’est la meme chose ought not to surprise us; in the vast scheme of things, civilization is a toddler. Men and women today may fly aircraft and text a friend in Mali, but under our electronic façade we have much more in common with our ancestors than just our DNA.

Take the recent election. By and large, Trump captured the rural and small-town vote; Hilary won many of the big cities. Here is Durant on the same split regarding Greece: “As in modern France and America, this great class of small proprietors is a steadying conservative force in a democracy where the propertyless city dwellers are always driving for reform…the freemen of the countryside tend to look down on the denizens of the city as either weak parasites or degraded slaves.” (Listen to Hank Williams Jr. “Country Boys Can Survive.”)

Here on page 270, while describing the Athenian diet, Durant writes “Water is the usual drink, but everyone has wine, for no civilization has found life tolerable without narcotics or stimulants.” Coffee, tea, wine, liquors of all kinds, beer, cigarettes, pot, and a long list of other narcotics: some condemn, rightfully in many cases, our addictions and pleasures, but perhaps they are the glue keeping the whole business functioning.

“The Greek,” Durant writes of ancient Athens, “might admit that honesty is the best policy, but he tries everything else first.” This might apply equally well to many of our politicians. And indeed, at the end of the paragraph, Durant adds “Perhaps, however, the Greeks differ from ourselves not in conduct but in candor; our greater delicacy makes it offense to us to preach what we practice.”

In speaking of the cosmetic condiments employed by Athenian women to enhance their looks, Durant goes into detail about the creams, washes, oils, and perfumes used by these ladies, then ends with “Women remain the same, because men do.”

Of Athenian industry, Durant writes “No machinery is available, but slaves can be had in abundance; it is because muscle power is so cheap that there is no incentive to develop machinery.” We see this same principle coming into play more and more in our country. As minimum wages rise, grocery stores, many restaurants, and other parts of the service industry have turned more and more to robots to serve their customers. I look, for example, at the self-service checkout aisle at my local grocery store, where one employee has charge of six checkout counters, and wonder why the store doesn’t install another of these.

Finally, our vanity remains. We still take pride in how others view us, which contrary to some I know I judge to be a good thing. We do care what others think of our appearance, though we often don’t show that we care. We even care how we are perceived in death, as most corpses in open casket funeral services wear a suit or a fine dress rather than their favorite pair of ratty pajamas.

Apparently, the Greeks cared too. “Plutarch,” Durant tells us, “tells a pretty story of how an epidemic of suicide among the women of Miletus was suddenly and completely ended by an ordinance decreeing that self-slain women should be carried naked through the marketplace to their funeral.”

Here on page 270, while describing the Athenian diet, Durant writes “Water is the usual drink, but everyone has wine, for no civilization has found life tolerable without narcotics or stimulants.” Coffee, tea, wine, liquors of all kinds, beer, cigarettes, pot, and a long list of other narcotics: some condemn, rightfully in many cases, our addictions and pleasures, but perhaps they are the glue keeping the whole business functioning.

“The Greek,” Durant writes of ancient Athens, “might admit that honesty is the best policy, but he tries everything else first.” This might apply equally well to many of our politicians. And indeed, at the end of the paragraph, Durant adds “Perhaps, however, the Greeks differ from ourselves not in conduct but in candor; our greater delicacy makes it offense to us to preach what we practice.”

In speaking of the cosmetic condiments employed by Athenian women to enhance their looks, Durant goes into detail about the creams, washes, oils, and perfumes used by these ladies, then ends with “Women remain the same, because men do.”

Of Athenian industry, Durant writes “No machinery is available, but slaves can be had in abundance; it is because muscle power is so cheap that there is no incentive to develop machinery.” We see this same principle coming into play more and more in our country. As minimum wages rise, grocery stores, many restaurants, and other parts of the service industry have turned more and more to robots to serve their customers. I look, for example, at the self-service checkout aisle at my local grocery store, where one employee has charge of six checkout counters, and wonder why the store doesn’t install another of these.

Finally, our vanity remains. We still take pride in how others view us, which contrary to some I know I judge to be a good thing. We do care what others think of our appearance, though we often don’t show that we care. We even care how we are perceived in death, as most corpses in open casket funeral services wear a suit or a fine dress rather than their favorite pair of ratty pajamas.

Apparently, the Greeks cared too. “Plutarch,” Durant tells us, “tells a pretty story of how an epidemic of suicide among the women of Miletus was suddenly and completely ended by an ordinance decreeing that self-slain women should be carried naked through the marketplace to their funeral.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed