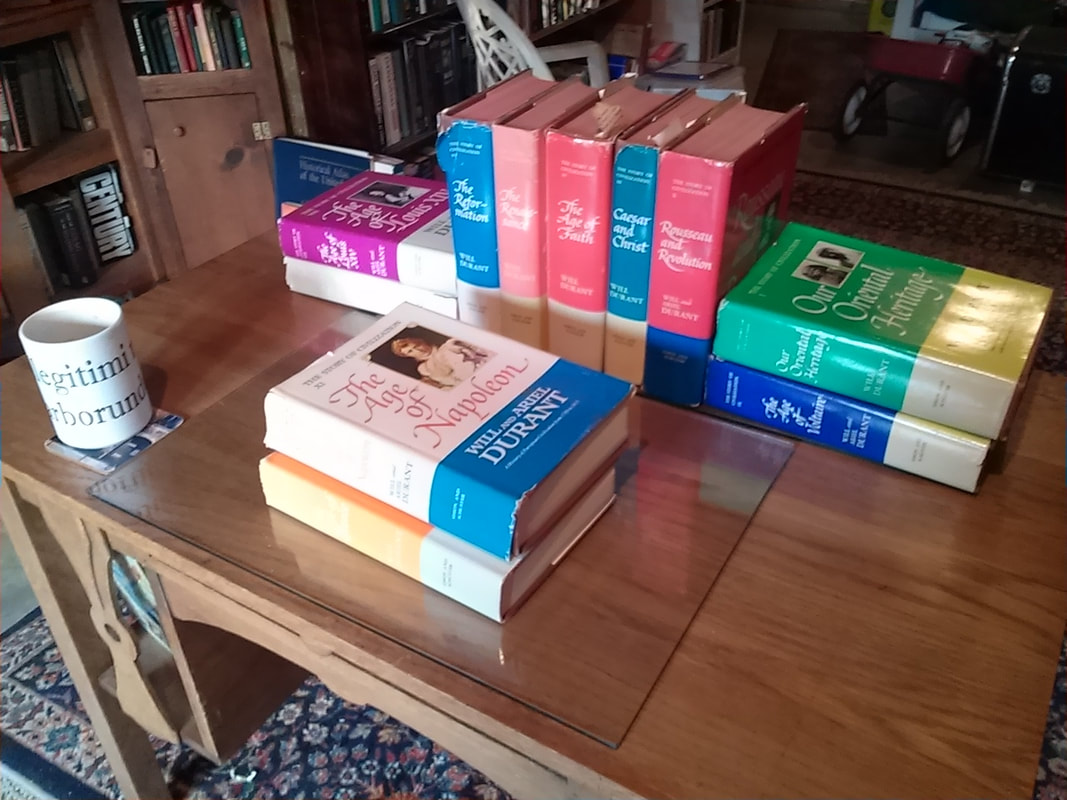

Today, March 1, I finished The Life of Greece, the second volume in Will Durant’s The Story of Civilization.

Though I was familiar in a general way with Ancient Greece—the great thinkers, writers, and sculptors, the struggled with the Persians and then with one another, the advances in mathematics, science, and astronomy—I was ignorant of the Hellenistic Period, those centuries following the demise of the Greek city-states.

Though I was familiar in a general way with Ancient Greece—the great thinkers, writers, and sculptors, the struggled with the Persians and then with one another, the advances in mathematics, science, and astronomy—I was ignorant of the Hellenistic Period, those centuries following the demise of the Greek city-states.

So here I received a quick education—quick because as I said at the beginning of this project, I intend to read these histories as I might read fiction, following the story but not memorizing dates, names, battles, and so on. In school, with the exception of a fine Byzantine history course in college, I never looked at the influence of the Greeks after Athens and Sparta had torn each other to pieces. I knew Alexander the Great had spread Greek ideas to the East while bringing back Oriental ideas to the West.

But I had never realized how many hundreds of colonies and outposts Greeks had established throughout the Mediterranean. These traders, explorers, and colonists brought Greek culture to Egypt and the rest of North Africa, to Palestine, to parts of the Black Sea, to Asia Minor (now Turkey). This establishment of Greek culture outside of Greece had enormous ramifications. “For a century,” Durant writes, “western Asia belonged to Europe. The way was prepared for the Pax Romana, and the embracing synthesis of Christendom.”

In the book’s final chapter, Durant reminds us of “Our Greek Heritage,” pointing out that Western imperialism of the last two hundred years gave that heritage to the world:

“Civilization does not die, it migrates; it changes its habitat and its dress, but it lives on. The decay of one civilization, as of one individual, makes room for the growth of another; life sheds the old skin, and surprises death with fresh youth. Greek civilization is alive; it moves in every breath of mind that we breathe; so much of it remains that none of us in one lifetime could absorb it all.”

On to Rome.

But I had never realized how many hundreds of colonies and outposts Greeks had established throughout the Mediterranean. These traders, explorers, and colonists brought Greek culture to Egypt and the rest of North Africa, to Palestine, to parts of the Black Sea, to Asia Minor (now Turkey). This establishment of Greek culture outside of Greece had enormous ramifications. “For a century,” Durant writes, “western Asia belonged to Europe. The way was prepared for the Pax Romana, and the embracing synthesis of Christendom.”

In the book’s final chapter, Durant reminds us of “Our Greek Heritage,” pointing out that Western imperialism of the last two hundred years gave that heritage to the world:

“Civilization does not die, it migrates; it changes its habitat and its dress, but it lives on. The decay of one civilization, as of one individual, makes room for the growth of another; life sheds the old skin, and surprises death with fresh youth. Greek civilization is alive; it moves in every breath of mind that we breathe; so much of it remains that none of us in one lifetime could absorb it all.”

On to Rome.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed