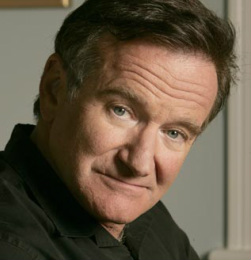

The suicide of Robin Williams has rightly brought out tributes from many people lauding his comedic genius and acting abilities. Since the 1970s, Williams was one of our premier celebrities, first on television and then in film. Several of his movies remain among my all-time favorites.

Williams’ death also has a more personal meaning to me. He was my age when he took his own life yesterday...

What Dreams May Come

The suicide of Robin Williams has rightly brought out tributes from many people lauding his comedic genius and acting abilities. Since the 1970s, Williams was one of our premier celebrities, first on television and then in film. Several of his movies remain among my all-time favorites.

Williams’ death also has a more personal meaning to me. He was my age when he took his own life yesterday. In the New York Daily News, a scholar and a student of suicide, Jennifer Hecht, reports on her own flirtation with self-destruction and on the long-recognized phenomenon of copycat suicides, particularly by people of the same gender and age as the victim. Like Jennifer Hecht and many others, I have entertained, particularly in my younger years, the idea of killing myself—and my self—finding on some of these occasions a comfort in the thought along the lines of “Ah well, I can always pull the trigger.” To paraphrase Nietzsche, the thought of suicide can get some of us through many a long night.

But to commit suicide, I also recognized, is to create a gaping hole of pain and bewilderment among those left behind. The worst case of suicide of which I have intimate knowledge involved a man who shot himself to death in a wooded park while his child celebrated a birthday at home. To do that to a child, no matter how deep your anguish, is to my way of thinking unbearably cruel and sad. For this reason alone—and there are others—suicide is not an option for me. I suspect it never was.

What has surprised me about this particular death is the reaction online. I read only two or three blogs, where both the bloggers and their readers speculated and then argued, sometimes viciously, about why Robin Williams killed himself. He was chronically depressed. He was bipolar. He was addicted to drugs. His worldview was dark. He didn’t believe in God. The list went on and on, and back and forth the opinions flew, sometimes compassionate, sometimes snarky, and sometimes just plain silly. (My favorite was the Catholic mother who was considering going off Facebook for a week as a sign of mourning. Not exactly sackcloth and ashes).

We humans like explanations, but the truth is no one knows and no one will ever know why Robin Williams committed suicide. Doubtless there is some truth in all of the above explanations, or in some of them, but we’ll never know for sure. There are simply too many shadows in the human self, too many facets to an individual’s personhood, for us to understand these things. We are enigmas, to others and to ourselves. Especially to ourselves. We can say, for example, that a man who leaps to his death when the market crashes did so because of his financial losses, but how then how do we explain the man in the next office who continued to work and hope in the future? Too many factors are at play for any real answer.

It is likely that Robin Williams himself didn’t know precisely why he committed suicide. Had someone been there to ask him, he might have felt foolish trying to come up with a reply. Even the words, “Because I can’t take it anymore,” don’t really work. At another moment in time, even later that day, those same words might have seemed overwrought and ridiculous to him.

Instead of wrangling over unanswerable questions regarding the why of Williams’ suicide, we might instead look at ourselves and at those around us, and affirm our reasons for living. Near the end of her article, Hecht writes that “it makes sense to decide now that you are not going to let your worst mood murder all your others. Practice having faith in your future self. Trust that he or she will know some things you do not know.”

Too often we fall into the trap mentioned by Hecht. We let our worst mood murder all the others. We let a grim day destroy all that is good and true and beautiful in our lives. Certainly, as Hecht writes, we do best when we have faith in our future selves.

But I would go a step farther. I would add that we must seek to love fiercely and wholeheartedly this mystery in which we live. A few fortunate souls may be born with this capacity for love, but the rest of us must work to find the beauty of this mystery and the love that lies at its heart. We may not always appreciate our world and those in it, and we will make mistakes and sometimes we will pay a tremendous price for our mistakes, but if we can remember the love and the mystery that surround us and live inside us, then we will want to stay and engage the world.

In the words of Ernest Hemingway, who later took his own life, “The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I would hate very much to leave it.”

Life is worth fighting for. Be a fighter. Be a lover. And never despair.

Williams’ death also has a more personal meaning to me. He was my age when he took his own life yesterday. In the New York Daily News, a scholar and a student of suicide, Jennifer Hecht, reports on her own flirtation with self-destruction and on the long-recognized phenomenon of copycat suicides, particularly by people of the same gender and age as the victim. Like Jennifer Hecht and many others, I have entertained, particularly in my younger years, the idea of killing myself—and my self—finding on some of these occasions a comfort in the thought along the lines of “Ah well, I can always pull the trigger.” To paraphrase Nietzsche, the thought of suicide can get some of us through many a long night.

But to commit suicide, I also recognized, is to create a gaping hole of pain and bewilderment among those left behind. The worst case of suicide of which I have intimate knowledge involved a man who shot himself to death in a wooded park while his child celebrated a birthday at home. To do that to a child, no matter how deep your anguish, is to my way of thinking unbearably cruel and sad. For this reason alone—and there are others—suicide is not an option for me. I suspect it never was.

What has surprised me about this particular death is the reaction online. I read only two or three blogs, where both the bloggers and their readers speculated and then argued, sometimes viciously, about why Robin Williams killed himself. He was chronically depressed. He was bipolar. He was addicted to drugs. His worldview was dark. He didn’t believe in God. The list went on and on, and back and forth the opinions flew, sometimes compassionate, sometimes snarky, and sometimes just plain silly. (My favorite was the Catholic mother who was considering going off Facebook for a week as a sign of mourning. Not exactly sackcloth and ashes).

We humans like explanations, but the truth is no one knows and no one will ever know why Robin Williams committed suicide. Doubtless there is some truth in all of the above explanations, or in some of them, but we’ll never know for sure. There are simply too many shadows in the human self, too many facets to an individual’s personhood, for us to understand these things. We are enigmas, to others and to ourselves. Especially to ourselves. We can say, for example, that a man who leaps to his death when the market crashes did so because of his financial losses, but how then how do we explain the man in the next office who continued to work and hope in the future? Too many factors are at play for any real answer.

It is likely that Robin Williams himself didn’t know precisely why he committed suicide. Had someone been there to ask him, he might have felt foolish trying to come up with a reply. Even the words, “Because I can’t take it anymore,” don’t really work. At another moment in time, even later that day, those same words might have seemed overwrought and ridiculous to him.

Instead of wrangling over unanswerable questions regarding the why of Williams’ suicide, we might instead look at ourselves and at those around us, and affirm our reasons for living. Near the end of her article, Hecht writes that “it makes sense to decide now that you are not going to let your worst mood murder all your others. Practice having faith in your future self. Trust that he or she will know some things you do not know.”

Too often we fall into the trap mentioned by Hecht. We let our worst mood murder all the others. We let a grim day destroy all that is good and true and beautiful in our lives. Certainly, as Hecht writes, we do best when we have faith in our future selves.

But I would go a step farther. I would add that we must seek to love fiercely and wholeheartedly this mystery in which we live. A few fortunate souls may be born with this capacity for love, but the rest of us must work to find the beauty of this mystery and the love that lies at its heart. We may not always appreciate our world and those in it, and we will make mistakes and sometimes we will pay a tremendous price for our mistakes, but if we can remember the love and the mystery that surround us and live inside us, then we will want to stay and engage the world.

In the words of Ernest Hemingway, who later took his own life, “The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I would hate very much to leave it.”

Life is worth fighting for. Be a fighter. Be a lover. And never despair.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed