Leon Battista Alberti, a figure totally unfamiliar to me, was a Renaissance man to the core. He was handsome and strong, could leap with his feet tied over a standing man, tamed wild horses and climbed mountains. He was a fine singer, a powerful orator, and “a skilled practitioner, in a dozen fields—mathematics, mechanics, architecture, sculpture, painting, music, poetry, drama, philosophy, civil and canon law.”

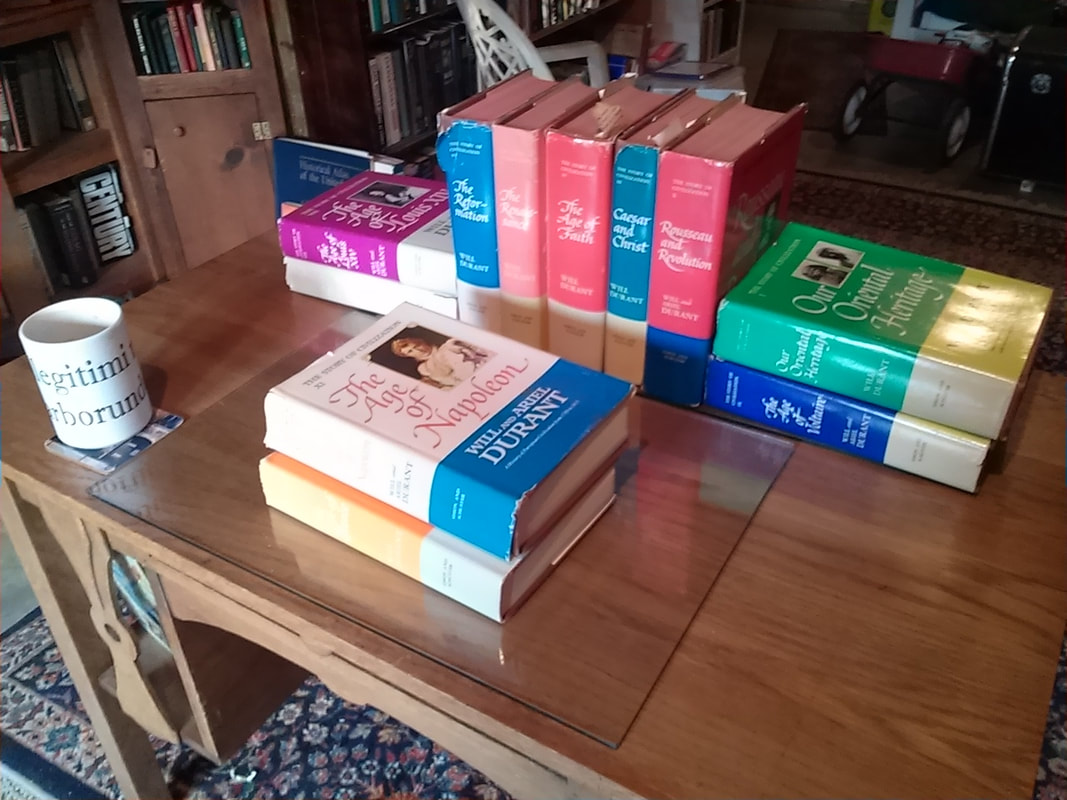

I am 135 pages into Will and Ariel Durant’s The Renaissance, and am struck by the differences between the educated young people of that era versus our own. In some ways, the scholars and artists of the Renaissance matured much earlier. Lorenzo de Medici, for example, was twenty years old when his father died and a committee of leading Florentine citizens called on the youth to assume the guidance of the state. Botticelli had set up his own studio by the time he was twenty. Those who went to school ranged from royalty to the sons of butchers, and some of these became renowned scholars at an early age. Education in 1500 was much more concentrated than now, of course, focusing on fewer subjects. (The raucous students of that era would have laughed at courses in sex education, taking their lessons in that subject from teachers outside of a classroom.)

Today’s students, on the other hand, face a body of knowledge that dwarves the information in the hands of Renaissance scholars. From lack of time alone, no one today could duplicate Alberti’s expertise in so many varied fields. We do apply the honorific “Renaissance Man” to someone at ease in several fields, an architect, for instance, who can quote Shakespeare and Plato, plays the violin, and has hiked the Appalachian Trail, yet ours is the age of specialization. A single lifetime does not allow us to participate on so many playing fields.

Our methods of education also have produced different results. The idea of childhood as some sort of idyllic time of play was non-existent during the days of Botticelli and Thomas More. From what I can detect, childhood in the Renaissance ended at between the ages of five and seven. Those who were then educated—and many were given such an opportunity—learned difficult topics under the threat of the teacher’s lash. They were also taught the Christian faith, just as millions today are taught a secular faith, but the Renaissance students also practiced a critical thinking of the kind so touted by today’s educators.

Of course, such comparisons need to be hedged by noting that despite the ubiquitous village schools and the universities ranging from Bologna to Oxford, most people of the Renaissance were semi-literate at best. (So are many Americans, but we’ll let that pass.) Education then was far less structured than what today, more hit-and-miss, less regimented in terms of advance.

Still, as I read about these students who lived six hundred years ago, I wonder about our expectations for our young people. Today many “experts” declare that true adulthood doesn’t begin until the age of 25, an age when Renaissance men and women of all classes were already well launched into earning a living and raising their families. Is our current predilection for a prolonged adolescence necessarily beneficial, or might it result in a lifelong childhood?

I know a good number of adults who by the age of twenty-two are already out and about in the world, taking risks, earning a living, married and even raising children. After traveling through the Durants for the last three days, I would say this to any young readers of this column: Expect more of yourself. Raise the bar. Grow every day. Push yourself to learn, to develop your talents and acquire new skills.

If you have a zeal for learning and undertaking challenges, and if you look at life as an adventure instead of a slog, then don’t hold back. Press forward and see what happens.

Today’s students, on the other hand, face a body of knowledge that dwarves the information in the hands of Renaissance scholars. From lack of time alone, no one today could duplicate Alberti’s expertise in so many varied fields. We do apply the honorific “Renaissance Man” to someone at ease in several fields, an architect, for instance, who can quote Shakespeare and Plato, plays the violin, and has hiked the Appalachian Trail, yet ours is the age of specialization. A single lifetime does not allow us to participate on so many playing fields.

Our methods of education also have produced different results. The idea of childhood as some sort of idyllic time of play was non-existent during the days of Botticelli and Thomas More. From what I can detect, childhood in the Renaissance ended at between the ages of five and seven. Those who were then educated—and many were given such an opportunity—learned difficult topics under the threat of the teacher’s lash. They were also taught the Christian faith, just as millions today are taught a secular faith, but the Renaissance students also practiced a critical thinking of the kind so touted by today’s educators.

Of course, such comparisons need to be hedged by noting that despite the ubiquitous village schools and the universities ranging from Bologna to Oxford, most people of the Renaissance were semi-literate at best. (So are many Americans, but we’ll let that pass.) Education then was far less structured than what today, more hit-and-miss, less regimented in terms of advance.

Still, as I read about these students who lived six hundred years ago, I wonder about our expectations for our young people. Today many “experts” declare that true adulthood doesn’t begin until the age of 25, an age when Renaissance men and women of all classes were already well launched into earning a living and raising their families. Is our current predilection for a prolonged adolescence necessarily beneficial, or might it result in a lifelong childhood?

I know a good number of adults who by the age of twenty-two are already out and about in the world, taking risks, earning a living, married and even raising children. After traveling through the Durants for the last three days, I would say this to any young readers of this column: Expect more of yourself. Raise the bar. Grow every day. Push yourself to learn, to develop your talents and acquire new skills.

If you have a zeal for learning and undertaking challenges, and if you look at life as an adventure instead of a slog, then don’t hold back. Press forward and see what happens.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed