It’s mid-August, and my days are crammed with syllabi, lesson planning, meetings and phone calls with parents, setting up the classroom, and collecting fees.

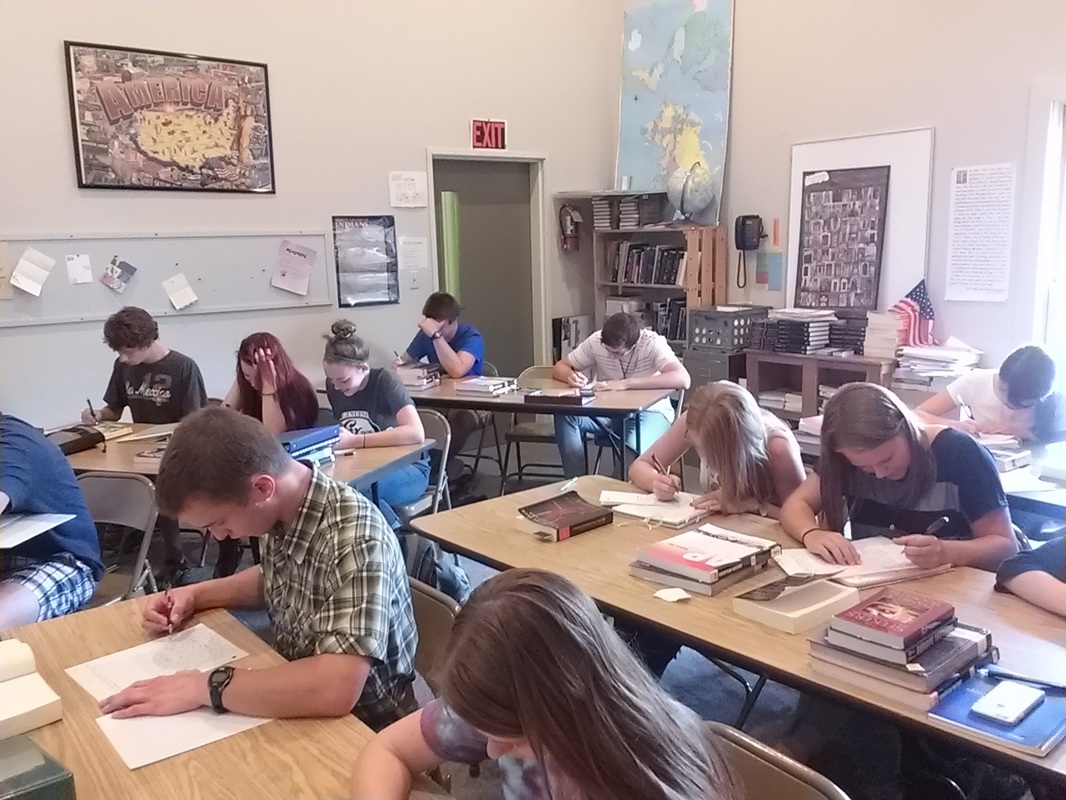

For the last twenty-six years, I have taught hundreds of home-educated students, including my own children. (My checkered teaching career also includes a semester in a university, two years in a prison, and two years in a public high school). For the last fifteen years, I have conducted these classes for homeschoolers in the Asheville area, offering instruction in literature, history, Latin, and composition. The students gather once a week for a two hour class and then return to their homes with work ranging from an additional four to seven hours, depending on the subject. For example, a student taking Latin III and AP English Language and Composition would attend two separate two-hour classes, and would then complete at home about four hours of work for Latin III and four or five hours for the Composition class.

Despite the labor involved—I typically teach twenty-four hours per week and spend another twenty-five hours or more grading papers and tests, answering emails, and preparing lessons—this work gives me a great deal of satisfaction. Many of these young people attend classes for five and six years in a row, advancing from basic composition courses to subjects like Advanced Placement Literature or Advanced Placement European History. These lengthy enrollments allow me to become well-acquainted with them and with their families, and afford me the marvelous opportunity of watching students grow physically, emotionally, and intellectually into young adults.

Along with my other preparations for a new academic year, every summer I ponder what I want my students to take away from my classes, and every summer the same answers come to me. If they can take hold of some or all of these ideas and put them into practice, then the year will have been a success.

First is the realization that writing and words are important. In every seminar, including the most basic Latin classes, I stress the importance of language and its uses. I explain to students that nearly every job and profession—public safety, medicine, law, nursing, engineering—depends mightily on clear communication. Using examples too lengthy for inclusion here, I demonstrate how an email or a letter written with beauty and power might bring them love and marriage, how a clear, concise resume might win them the job of their dreams.

The talk is easy, but the writing is hard on the students and on me. For the past ten years, more than 150 young people have annually joined these seminars, and most of them—the Latin students are the exception—write at least twenty papers, reports, and in-class essays between September and May. Some of them are required to keep journals; they memorize poetry to put words on their tongues; all of them must memorize vocabulary words; they learn grammar by having their compositions edited, often by Advanced Placement students I hire to make such corrections. The young people groan and sweat over their papers, and I groan and correct, but by this process writers are made. When you graduate high school having written 80 to 100 essays, you are ready for college.

And ready they are. Many of them become fine essayists, far more adept than I ever was at their age. Nothing delights me more than to have a former student tell me how these writing exercises made for a stellar performance in some freshman composition class. Several, including two seventeen year olds, have found work at their university’s writing centers, and one young fellow who joined the Marines received high compliments on a report he wrote for his sergeant, who was at first convinced that it was the work of the Marine’s girlfriend.

Reading is next on the agenda. This year my youngest students are reading books ranging from Cracker!: The Best Dog in Vietnam and The Essential Calvin and Hobbes to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (we read the play aloud in class). The Advanced Placement Literature class will tackle, among other books, Crime and Punishment, Othello, The Power and the Glory, and Wuthering Heights. In addition to various novels, plays, and histories, students in my British History and Literature seminars—I follow a three year cycle of World History, American History, and British History—read from an old, fat Prentice-Hall anthology, a treasure-box of poetry, history, and analysis.

Within just the past fifteen years, I have seen a marked decline in the reading of books among my students, a circumstance I attribute to our electronic culture. Fewer and fewer students are real readers. They have access to books on their gadgets, but prefer the vast playground of online entertainment to the requirements of time and concentration needed to complete a novel. We adults are no different. On visits to the coffee shop at our local Barnes and Noble, for example, I am always struck by how few of the customers are actually reading printed or electronic books, but are instead jabbing away at their iPads and laptops.

In addition, I have seen an increase in the number of students who prefer to read, when they do read, fantasy and science fiction. With the exception of Ray Bradbury in my younger years, I was never attracted to these two genres, a flaw in myself that some students doubtless regard as a deficit. This year, the younger class will read The Hobbit, another class will tackle Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man, and the older students will delve into Tolkien’s translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. But that excursion into fantasy is as far as I go.

That so many students currently enjoy fantasy suggests several things. First, writers are producing some excellent work for teens in this genre. Second, the stories and characters empower the students (Think Katniss Everdeen of The Hunger Games for the girls, Percy Jackson of The Lightning Thief for the boys). Finally, fantasy offers an escape from our news media with its daily and often hysterical pronouncements of catastrophe.

The study of history figures into this program of learning. In Josiah Bunting’s An Education For Our Time, which my Advanced Placement Composition students read for the novel’s vocabulary and formal style as well as for its remarks on education, the protagonist, a wealthy entrepreneur named John Adams, recommends that 30% of the college curriculum he is designing be devoted to the study of history. Not only can history teach us more about human nature, Bunting writes, but we can also learn the art of emulation by studying the great men and women of the past. In the old Roman sense, history can provide us with models by which we may improve our own character.

History also offers comfort to her students. Once, during the first year of the Obama administration, a young man in my class, who probably listened to too much talk radio, exclaimed that our country was declining and that the future looked bleak. “What can we do, Mr. Minick?” he plaintively asked.

“Quit listening to all the doomsayers,” I suggested. “Study your history. Lots of your ancestors had a tougher life than you.”

When students encounter and discuss events like the Black Death, the Reformation, or the Great War, and if those events can be brought to life for them, then they will have acquired one of the chief gifts of an historical education, which is the ability to take the long view. Human beings may fail to gather few concrete lessons from history, but students of history can at least look to the past and realize that their ancestors have suffered disasters and endured trials that make our own difficulties seem a walk in the park.

My last two hopes for my students are non-academic. First, I wish with all of my heart to inculcate in them self-discipline and a work ethic. Unlike their peers in formal classroom settings, who are daily goaded by teachers to complete their work, my students do the bulk of their lessons alone and at home. This situation offers an ideal means of developing certain values—commitment, preparation, self-motivation—that will serve them well in college and in life. Though every year brings failure in this area—some students are lazy or seek the easy way out of their assignments—most of these young people complete their work and come to class prepared. Many of them are unaware of the powerful tools they are creating in themselves until they go off to college or into the work place, and find themselves fully capable of meeting the challenges life throws at them.

Finally, I would hope that this study of history, of stories and poetry, and of Latin, would contribute to the formation of character in all those I teach. In Beauty Will Save The World, Gregory Wolfe writes that “...Hans Rookmaaker, the Dutch Calvinist art historian, once said, ‘Christ didn’t come to make us Christians. He came to make us fully human.’” Regarding literature and history, I am a student of the old school, believing as I do that familiarity with these subjects also helps make us fully human. To follow the tortured thoughts of Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, to read the zany antics of physicist and Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman in Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman, to discuss and debate the motivations of Roundheads and Cavaliers in the English Civil War, to have at least a passing acquaintance with the likes of Catullus, Caesar, and Virgil: these and many other pieces of literature and history give us words and ideals by which to live.

Sometimes I may push too hard or care too passionately. Once a student, exasperated by some remark I’d made, said from the back of the classroom, “Why do you care so much about us? We’re not your kids.”

“No,” I said, “you’re not my kids. But I have children and grandchildren, and they’re going to have to live in the world alongside of you.”

There are times when I grieve for that future world and fear for my grandchildren. Daily news reports—gang shootings in Chicago, binge drinking in college, the ignorance of our youth regarding their culture and history—affect me as they do others, and there are those nighttime hours when I give way to despair and wonder whether my I am doing any good at all, when the war seems lost and the education of these small platoons is wasted effort.

But in the classroom, when I observe Grace as she pores over an essay on A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, when I watch Frank, who loves acting and singing, recite the first sixteen lines of Chaucer’s “Prologue” to The Canterbury Tales, when I listen to the students debate the merits of Protestants and Catholics in the Reformation, I can’t help but feel gladdened. I would hope that some of what they have learned will assuage their future sorrows or add to their future joys, that the self-discipline which brought success in the classroom will bring them success in the future, and that they can make a difference in a dark and troubled world.

Despite the labor involved—I typically teach twenty-four hours per week and spend another twenty-five hours or more grading papers and tests, answering emails, and preparing lessons—this work gives me a great deal of satisfaction. Many of these young people attend classes for five and six years in a row, advancing from basic composition courses to subjects like Advanced Placement Literature or Advanced Placement European History. These lengthy enrollments allow me to become well-acquainted with them and with their families, and afford me the marvelous opportunity of watching students grow physically, emotionally, and intellectually into young adults.

Along with my other preparations for a new academic year, every summer I ponder what I want my students to take away from my classes, and every summer the same answers come to me. If they can take hold of some or all of these ideas and put them into practice, then the year will have been a success.

First is the realization that writing and words are important. In every seminar, including the most basic Latin classes, I stress the importance of language and its uses. I explain to students that nearly every job and profession—public safety, medicine, law, nursing, engineering—depends mightily on clear communication. Using examples too lengthy for inclusion here, I demonstrate how an email or a letter written with beauty and power might bring them love and marriage, how a clear, concise resume might win them the job of their dreams.

The talk is easy, but the writing is hard on the students and on me. For the past ten years, more than 150 young people have annually joined these seminars, and most of them—the Latin students are the exception—write at least twenty papers, reports, and in-class essays between September and May. Some of them are required to keep journals; they memorize poetry to put words on their tongues; all of them must memorize vocabulary words; they learn grammar by having their compositions edited, often by Advanced Placement students I hire to make such corrections. The young people groan and sweat over their papers, and I groan and correct, but by this process writers are made. When you graduate high school having written 80 to 100 essays, you are ready for college.

And ready they are. Many of them become fine essayists, far more adept than I ever was at their age. Nothing delights me more than to have a former student tell me how these writing exercises made for a stellar performance in some freshman composition class. Several, including two seventeen year olds, have found work at their university’s writing centers, and one young fellow who joined the Marines received high compliments on a report he wrote for his sergeant, who was at first convinced that it was the work of the Marine’s girlfriend.

Reading is next on the agenda. This year my youngest students are reading books ranging from Cracker!: The Best Dog in Vietnam and The Essential Calvin and Hobbes to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (we read the play aloud in class). The Advanced Placement Literature class will tackle, among other books, Crime and Punishment, Othello, The Power and the Glory, and Wuthering Heights. In addition to various novels, plays, and histories, students in my British History and Literature seminars—I follow a three year cycle of World History, American History, and British History—read from an old, fat Prentice-Hall anthology, a treasure-box of poetry, history, and analysis.

Within just the past fifteen years, I have seen a marked decline in the reading of books among my students, a circumstance I attribute to our electronic culture. Fewer and fewer students are real readers. They have access to books on their gadgets, but prefer the vast playground of online entertainment to the requirements of time and concentration needed to complete a novel. We adults are no different. On visits to the coffee shop at our local Barnes and Noble, for example, I am always struck by how few of the customers are actually reading printed or electronic books, but are instead jabbing away at their iPads and laptops.

In addition, I have seen an increase in the number of students who prefer to read, when they do read, fantasy and science fiction. With the exception of Ray Bradbury in my younger years, I was never attracted to these two genres, a flaw in myself that some students doubtless regard as a deficit. This year, the younger class will read The Hobbit, another class will tackle Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man, and the older students will delve into Tolkien’s translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. But that excursion into fantasy is as far as I go.

That so many students currently enjoy fantasy suggests several things. First, writers are producing some excellent work for teens in this genre. Second, the stories and characters empower the students (Think Katniss Everdeen of The Hunger Games for the girls, Percy Jackson of The Lightning Thief for the boys). Finally, fantasy offers an escape from our news media with its daily and often hysterical pronouncements of catastrophe.

The study of history figures into this program of learning. In Josiah Bunting’s An Education For Our Time, which my Advanced Placement Composition students read for the novel’s vocabulary and formal style as well as for its remarks on education, the protagonist, a wealthy entrepreneur named John Adams, recommends that 30% of the college curriculum he is designing be devoted to the study of history. Not only can history teach us more about human nature, Bunting writes, but we can also learn the art of emulation by studying the great men and women of the past. In the old Roman sense, history can provide us with models by which we may improve our own character.

History also offers comfort to her students. Once, during the first year of the Obama administration, a young man in my class, who probably listened to too much talk radio, exclaimed that our country was declining and that the future looked bleak. “What can we do, Mr. Minick?” he plaintively asked.

“Quit listening to all the doomsayers,” I suggested. “Study your history. Lots of your ancestors had a tougher life than you.”

When students encounter and discuss events like the Black Death, the Reformation, or the Great War, and if those events can be brought to life for them, then they will have acquired one of the chief gifts of an historical education, which is the ability to take the long view. Human beings may fail to gather few concrete lessons from history, but students of history can at least look to the past and realize that their ancestors have suffered disasters and endured trials that make our own difficulties seem a walk in the park.

My last two hopes for my students are non-academic. First, I wish with all of my heart to inculcate in them self-discipline and a work ethic. Unlike their peers in formal classroom settings, who are daily goaded by teachers to complete their work, my students do the bulk of their lessons alone and at home. This situation offers an ideal means of developing certain values—commitment, preparation, self-motivation—that will serve them well in college and in life. Though every year brings failure in this area—some students are lazy or seek the easy way out of their assignments—most of these young people complete their work and come to class prepared. Many of them are unaware of the powerful tools they are creating in themselves until they go off to college or into the work place, and find themselves fully capable of meeting the challenges life throws at them.

Finally, I would hope that this study of history, of stories and poetry, and of Latin, would contribute to the formation of character in all those I teach. In Beauty Will Save The World, Gregory Wolfe writes that “...Hans Rookmaaker, the Dutch Calvinist art historian, once said, ‘Christ didn’t come to make us Christians. He came to make us fully human.’” Regarding literature and history, I am a student of the old school, believing as I do that familiarity with these subjects also helps make us fully human. To follow the tortured thoughts of Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, to read the zany antics of physicist and Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman in Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman, to discuss and debate the motivations of Roundheads and Cavaliers in the English Civil War, to have at least a passing acquaintance with the likes of Catullus, Caesar, and Virgil: these and many other pieces of literature and history give us words and ideals by which to live.

Sometimes I may push too hard or care too passionately. Once a student, exasperated by some remark I’d made, said from the back of the classroom, “Why do you care so much about us? We’re not your kids.”

“No,” I said, “you’re not my kids. But I have children and grandchildren, and they’re going to have to live in the world alongside of you.”

There are times when I grieve for that future world and fear for my grandchildren. Daily news reports—gang shootings in Chicago, binge drinking in college, the ignorance of our youth regarding their culture and history—affect me as they do others, and there are those nighttime hours when I give way to despair and wonder whether my I am doing any good at all, when the war seems lost and the education of these small platoons is wasted effort.

But in the classroom, when I observe Grace as she pores over an essay on A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, when I watch Frank, who loves acting and singing, recite the first sixteen lines of Chaucer’s “Prologue” to The Canterbury Tales, when I listen to the students debate the merits of Protestants and Catholics in the Reformation, I can’t help but feel gladdened. I would hope that some of what they have learned will assuage their future sorrows or add to their future joys, that the self-discipline which brought success in the classroom will bring them success in the future, and that they can make a difference in a dark and troubled world.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed