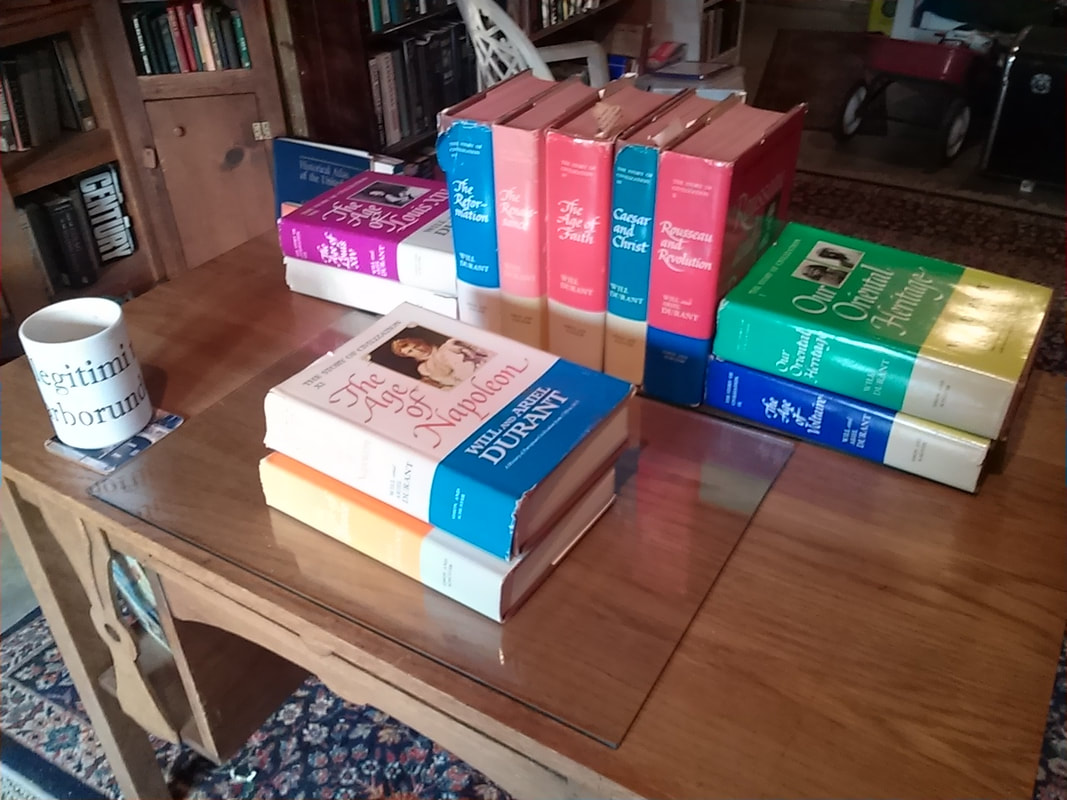

I am within 150 pages of the end of Volume IX of The Story of Civilization: The Age of Voltaire. Though I have fallen a little behind in my reading lately, I am confident, Deo volente, that I will finish this series by January 1, 2019, the date I set myself nine months ago.

Will and Ariel Durant’s account of the Enlightenment, that time from the very late sixteenth century up to the rumblings of Revolution in France, has left many impressions. Here are a few, for those of you interested.

Will and Ariel Durant’s account of the Enlightenment, that time from the very late sixteenth century up to the rumblings of Revolution in France, has left many impressions. Here are a few, for those of you interested.

First, Isaac Newton’s comment “If I have seen further it is from standing on the shoulders of giants” sums up the science of the Enlightenment vis-à-vis the science of our own day. The science of the eighteenth century was crude, of course, compared to own age, but by heavens these were people who provide those shoulders on which we now stand. Chemistry, physics, medicine, biology, anatomy, and a dozen other fields were all undergoing exploration. Given their primitive instruments, it is impressive to read of these explorers discovering and recording everything from pollination of plants to early theories of evolution.

Next up are the number of talents possessed by the men and women of this era. One example: Leonhard Euler “stands out as the most versatile and prolific mathematician of his time…eminent in mathematics, mechanics, optics, acoustics, hydrodynamics, astronomy, chemistry, and medicine, and knowing half the Aeneid by heart.”

Finally, it is remarkable how so many of the philosophes and scientists, so many of whom were Deists, were educated by Jesuits. As the Durants say of Diderot, whose Encyclopedie was the “most famous of all experiments in the popularization of knowledge” and whom they rank as “the most original thinker of his time,” “the Jesuits lost a novice by sharpening a mind.” This scenario is repeated over and over again, testifying to the enormous influence of Jesuitical education in France at that time.

So on I go.

Next up are the number of talents possessed by the men and women of this era. One example: Leonhard Euler “stands out as the most versatile and prolific mathematician of his time…eminent in mathematics, mechanics, optics, acoustics, hydrodynamics, astronomy, chemistry, and medicine, and knowing half the Aeneid by heart.”

Finally, it is remarkable how so many of the philosophes and scientists, so many of whom were Deists, were educated by Jesuits. As the Durants say of Diderot, whose Encyclopedie was the “most famous of all experiments in the popularization of knowledge” and whom they rank as “the most original thinker of his time,” “the Jesuits lost a novice by sharpening a mind.” This scenario is repeated over and over again, testifying to the enormous influence of Jesuitical education in France at that time.

So on I go.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed