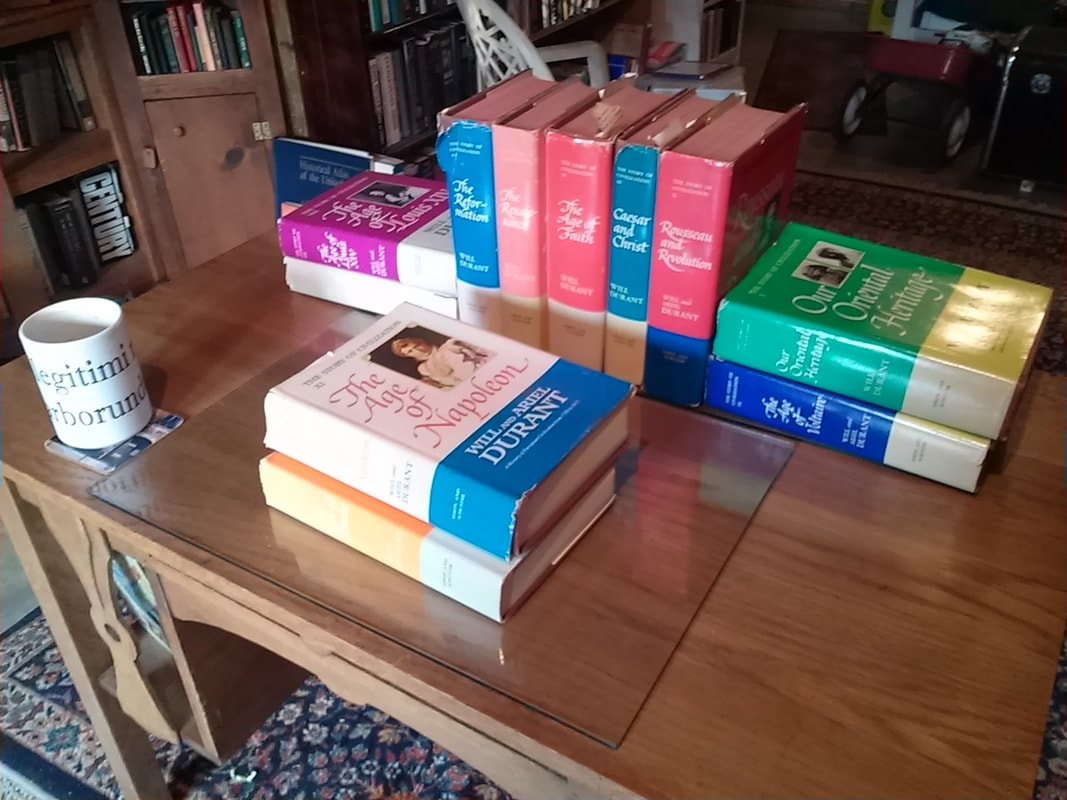

I have finished Will and Ariel Durant’s The Renaissance and am now well into The Reformation, which, as Durant makes clear in his introduction, not only showcases the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic response, but developments in Judaism and Islam as well.

In several ways, the artists of the Renaissance were very different from their modern counterparts. Many of these painters and sculptors rose from poverty by their talent; nearly all of them were men; some were a product of a time in which honor ran high and tempers short, and so were prone to violence; religious themes often dominated their works; scenes and figures from Greek and Roman myths often shared Christian paintings or stood on their own; the human body and the human being became the focus of brush and paint, mallet and chisel.

In several ways, the artists of the Renaissance were very different from their modern counterparts. Many of these painters and sculptors rose from poverty by their talent; nearly all of them were men; some were a product of a time in which honor ran high and tempers short, and so were prone to violence; religious themes often dominated their works; scenes and figures from Greek and Roman myths often shared Christian paintings or stood on their own; the human body and the human being became the focus of brush and paint, mallet and chisel.

Here is Durant on the subject near the end of this tome:

“Indeed, Renaissance painting was a sensual art, though it produced some of the greatest religious paintings, and—as on the Sistine ceiling—some of the most spiritual and sublime. But that sensuality was a wholesome reaction. The body had been vilified long enough; woman had borne through ungracious centuries the abuse of a harsh asceticism; it was good that life should reaffirm, and art enhance, the loveliness of healthy human forms. The Renaissance had tired of original sin, breast-beating, and mythical post-mortem terrors; it turned its back upon death, and its face to life; and long before Schiller and Beethoven, it sang an exhilarating, incomparable ode to joy.”

To compare Renaissance Italy to Post-Modernist America, not only the artists but also the writers, the clergy, and the professional and mercantile class, is fascinating. Renaissance writers, for example, often paid a stiff price for opposing the powers-that-be, the clergy and the nobility; though many poets and writers attacked both priest and duke, some were rewarded with death or exile. In America, authors who stray from the path are slandered online or howled down at speaking engagements. The Renaissance clergy from the top down dallied with mistresses, produced children, flirted with heresy, maneuvered in politics like Machiavelli, and led troops into war, all the while encouraging that sensual art Durant speaks of, that celebration of flesh which would eventually bring condemnation from dour Protestants. Today’s clergy leave from the public eye the mistresses, but find heresy as amenable as some of their Roman counterparts. (Indeed, the word heresy in our age is little used; we shun divisive language.) The professional classes of both eras are more similar, with the primary focus then and now being the accumulation of wealth.

An old saying “Comparisons are odious,” drives the thinking of some today. A negative comparison of, say, the culture of Ancient Greece to that of the Aborigine usually brings shrill denunciations. Delineating differences between male and female is verboten. And so on….

Nonetheless, I will make a few more comparisons between then and now, though I must first admit my ignorance regarding the world of art. I freely admit knowing almost nothing of painting and sculpture being produced in this year 2018.

On the other hand, let’s try a little experiment. Write out a list of artists you know from the Renaissance. (If nothing else, think of the Ninja Turtles.) Write out a list of Impressionists you remember. Write a list of any other artists that fall outside of these two schools who lived before our present era.

Now write down the names of all the artists—painters, sculptors, and I’ll even throw in photographers—living in the twenty-first century.

After reading Durant—and again, I easily admit my shambling ignorance—I would contend that the Renaissance art surpasses in beauty, form, magnitude, and craftsmanship the art produced today. The stupendous works of Michelangelo, Raphael, Titan, Da Vinci, and a score of other great painters and sculptors dwelt on Christian and Classical themes. The artists joined Christian beliefs and legends with the myths and forms of Greece and Rome. Though some of them were religious skeptics, they painted scenes from the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary, the saints, because their patrons, often the popes and bishops of the Church, demanded of them that work and because they lived in an era still immersed in that Faith. But they also either brought classic themes and forms into these paintings, or else painted separately canvases depicting the myths of the Ancients.

Jerusalem and Ancient Rome: these were—and are, whatever we may think today—the cornerstones of the Renaissance and of Western civilization.

Which brings us to a perplexity: Can great art be produced without belief of some kind in God, or at least, without an appreciation of the wonder and mystery of our whirling planet? Can great art ignore its own past?

“Indeed, Renaissance painting was a sensual art, though it produced some of the greatest religious paintings, and—as on the Sistine ceiling—some of the most spiritual and sublime. But that sensuality was a wholesome reaction. The body had been vilified long enough; woman had borne through ungracious centuries the abuse of a harsh asceticism; it was good that life should reaffirm, and art enhance, the loveliness of healthy human forms. The Renaissance had tired of original sin, breast-beating, and mythical post-mortem terrors; it turned its back upon death, and its face to life; and long before Schiller and Beethoven, it sang an exhilarating, incomparable ode to joy.”

To compare Renaissance Italy to Post-Modernist America, not only the artists but also the writers, the clergy, and the professional and mercantile class, is fascinating. Renaissance writers, for example, often paid a stiff price for opposing the powers-that-be, the clergy and the nobility; though many poets and writers attacked both priest and duke, some were rewarded with death or exile. In America, authors who stray from the path are slandered online or howled down at speaking engagements. The Renaissance clergy from the top down dallied with mistresses, produced children, flirted with heresy, maneuvered in politics like Machiavelli, and led troops into war, all the while encouraging that sensual art Durant speaks of, that celebration of flesh which would eventually bring condemnation from dour Protestants. Today’s clergy leave from the public eye the mistresses, but find heresy as amenable as some of their Roman counterparts. (Indeed, the word heresy in our age is little used; we shun divisive language.) The professional classes of both eras are more similar, with the primary focus then and now being the accumulation of wealth.

An old saying “Comparisons are odious,” drives the thinking of some today. A negative comparison of, say, the culture of Ancient Greece to that of the Aborigine usually brings shrill denunciations. Delineating differences between male and female is verboten. And so on….

Nonetheless, I will make a few more comparisons between then and now, though I must first admit my ignorance regarding the world of art. I freely admit knowing almost nothing of painting and sculpture being produced in this year 2018.

On the other hand, let’s try a little experiment. Write out a list of artists you know from the Renaissance. (If nothing else, think of the Ninja Turtles.) Write out a list of Impressionists you remember. Write a list of any other artists that fall outside of these two schools who lived before our present era.

Now write down the names of all the artists—painters, sculptors, and I’ll even throw in photographers—living in the twenty-first century.

After reading Durant—and again, I easily admit my shambling ignorance—I would contend that the Renaissance art surpasses in beauty, form, magnitude, and craftsmanship the art produced today. The stupendous works of Michelangelo, Raphael, Titan, Da Vinci, and a score of other great painters and sculptors dwelt on Christian and Classical themes. The artists joined Christian beliefs and legends with the myths and forms of Greece and Rome. Though some of them were religious skeptics, they painted scenes from the life of Christ, the Virgin Mary, the saints, because their patrons, often the popes and bishops of the Church, demanded of them that work and because they lived in an era still immersed in that Faith. But they also either brought classic themes and forms into these paintings, or else painted separately canvases depicting the myths of the Ancients.

Jerusalem and Ancient Rome: these were—and are, whatever we may think today—the cornerstones of the Renaissance and of Western civilization.

Which brings us to a perplexity: Can great art be produced without belief of some kind in God, or at least, without an appreciation of the wonder and mystery of our whirling planet? Can great art ignore its own past?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed