Every once in a great while, I come away from a book like some near-sighted fourth grader who has just put on his first pair of glasses. The math problems on the whiteboard leap out at him; the words in his Open Court Reader are no longer a blur; the dimple in Jeannie Godine’s cheek is as fetching as her voice. I can see, the kid says to himself. I can really see.

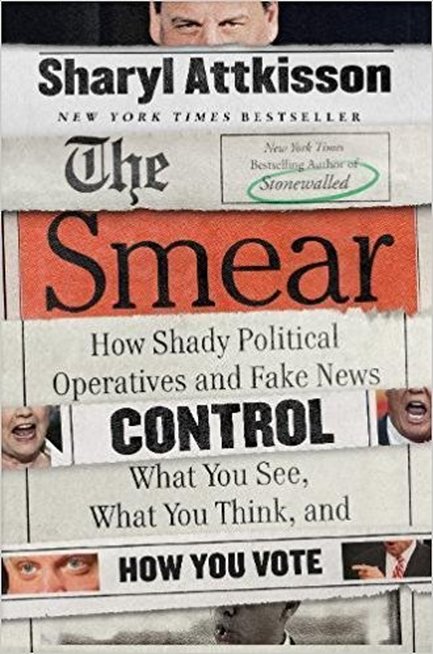

Sharyl Atkisson’s The Smear: How Shady Political Operatives and Fake News Control What You See, What You Think, and How You Vote (Harper, 2017, 304 pages) is that book. After finishing the last page, I felt as though some ophthalmologist had worked her laser magic, burning away cataracts and giving me new eyes.

Unlike my fictional fourth-grader, however, I was appalled and sickened by what I saw, which was Attkisson’s intention. Horror fiction has never appealed to me, but Atkisson’s dissection of political manipulation and fake news left me far more creeped-out than any Stephen King novel. Grim as it was to read, The Smear left me with a resolution: I will never again accept any story from any online or national news story at face value.

In this investigative triumph, Attkisson rips away the mask of what passes for news today, revealing how those in power or with an agenda spend billions a year to vilify opponents and dupe the rest of us. Corporations, political groups, think tanks, nonprofits, super PACs, and various online sites deal out lies and half-lies, and if necessary, invent rumors that will fly from New York to Los Angeles before the truth has gotten out of bed.

These smear artists practice many tricks. They pack debate halls with their candidate’s supporters. They set up barriers between their candidates or sponsors to conceal the source of their slanders. They take a quotation out of context and run it as a headline or even as the gist of an article. Just yesterday, for example, wildly excited reporters told us that the head of our nuclear forces would refuse to take launch orders from President Trump. Today we learned that the general had said no such thing, that he correctly said he would refuse illegal orders to launch nuclear missiles, and that the “reporters” had taken his remark out of context, entirely changing his meaning.

As Attkisson makes abundantly clear, and as most who follow online news know, such fabrications occur daily on the Internet. In The Smear, we learn that these mendacities are deliberate. Thousands of people and billions of bucks work hard to make these mud-pies, hoping to enhance a candidate or a cause by slinging dirt at the opposition. David Brock of Media Matters, painted here by Attkisson as the king of sleaze, takes the heaviest of her cannonades, but many others, operatives in both progressive and conservative camps, come into her sights.

Especially disheartening is Attkisson’s examination of papers like The New York Times and The Washington Post. We expect the nuts, cranks, and liars on the Internet, but once upon a time we could open a major paper or turn on the television, and find real journalism. Reporters double-checked sources, tracked down leads, made telephone calls, talked to the people involved in the story. Now, as Attkisson points out, many reporters not only skip these requisites, but some of them concoct their stories from the same online resources read by the rest of us.

We see this technique at play everywhere today. In just the past two weeks—I am writing this column on November 20, 2017—various politicians, candidates for office, journalists, and Hollywood figures have come under fire for sexual assault, with some of the charges dating back thirty years. Rather than abiding by the idea that we are innocent until found guilty, a mob of baying pundits is demanding the accused withdraw from public life and don ashes-and-sackcloth in repentance. The accusations, true or not, gain credence. Repeat the lie often enough, and the lie becomes the truth.

In analyzing these smears, Attkisson takes an even-handed approach. She gives us details, citing sources and naming names, offering a screed against neither the left nor the right, but instead demonstrating that both sides have sticky fingers and dirty hands.

Attkisson also shows us the fate of some of the victims of the smear. They are ostracized, dismissed from their posts, regarded awry by their friends. Julian Assange of WikiLeaks; Neil Clark, a British journalist of the left now smeared by the left; a fraternity at the University of Virginia: these and many others have suffered from lies and distortions.

In the USSR, savvy Russians understood that the main newspaper, Pravda (Truth), routinely distorted the news. They learned to “read between the lines” to dig out the real truth. At the end of The Smear, Attkisson calls on Americans to do the same with our own media. She writes, “…one thing you can count on is that most every image that crosses your path has been put there for a reason. Nothing happens by accident. What you need to ask yourself isn’t so much Is it true, but Who wants me to believe it—and why?”

An early New Year’s resolution: I intend to remember this book every day before visiting my usual news sites.

Every day.

Unlike my fictional fourth-grader, however, I was appalled and sickened by what I saw, which was Attkisson’s intention. Horror fiction has never appealed to me, but Atkisson’s dissection of political manipulation and fake news left me far more creeped-out than any Stephen King novel. Grim as it was to read, The Smear left me with a resolution: I will never again accept any story from any online or national news story at face value.

In this investigative triumph, Attkisson rips away the mask of what passes for news today, revealing how those in power or with an agenda spend billions a year to vilify opponents and dupe the rest of us. Corporations, political groups, think tanks, nonprofits, super PACs, and various online sites deal out lies and half-lies, and if necessary, invent rumors that will fly from New York to Los Angeles before the truth has gotten out of bed.

These smear artists practice many tricks. They pack debate halls with their candidate’s supporters. They set up barriers between their candidates or sponsors to conceal the source of their slanders. They take a quotation out of context and run it as a headline or even as the gist of an article. Just yesterday, for example, wildly excited reporters told us that the head of our nuclear forces would refuse to take launch orders from President Trump. Today we learned that the general had said no such thing, that he correctly said he would refuse illegal orders to launch nuclear missiles, and that the “reporters” had taken his remark out of context, entirely changing his meaning.

As Attkisson makes abundantly clear, and as most who follow online news know, such fabrications occur daily on the Internet. In The Smear, we learn that these mendacities are deliberate. Thousands of people and billions of bucks work hard to make these mud-pies, hoping to enhance a candidate or a cause by slinging dirt at the opposition. David Brock of Media Matters, painted here by Attkisson as the king of sleaze, takes the heaviest of her cannonades, but many others, operatives in both progressive and conservative camps, come into her sights.

Especially disheartening is Attkisson’s examination of papers like The New York Times and The Washington Post. We expect the nuts, cranks, and liars on the Internet, but once upon a time we could open a major paper or turn on the television, and find real journalism. Reporters double-checked sources, tracked down leads, made telephone calls, talked to the people involved in the story. Now, as Attkisson points out, many reporters not only skip these requisites, but some of them concoct their stories from the same online resources read by the rest of us.

We see this technique at play everywhere today. In just the past two weeks—I am writing this column on November 20, 2017—various politicians, candidates for office, journalists, and Hollywood figures have come under fire for sexual assault, with some of the charges dating back thirty years. Rather than abiding by the idea that we are innocent until found guilty, a mob of baying pundits is demanding the accused withdraw from public life and don ashes-and-sackcloth in repentance. The accusations, true or not, gain credence. Repeat the lie often enough, and the lie becomes the truth.

In analyzing these smears, Attkisson takes an even-handed approach. She gives us details, citing sources and naming names, offering a screed against neither the left nor the right, but instead demonstrating that both sides have sticky fingers and dirty hands.

Attkisson also shows us the fate of some of the victims of the smear. They are ostracized, dismissed from their posts, regarded awry by their friends. Julian Assange of WikiLeaks; Neil Clark, a British journalist of the left now smeared by the left; a fraternity at the University of Virginia: these and many others have suffered from lies and distortions.

In the USSR, savvy Russians understood that the main newspaper, Pravda (Truth), routinely distorted the news. They learned to “read between the lines” to dig out the real truth. At the end of The Smear, Attkisson calls on Americans to do the same with our own media. She writes, “…one thing you can count on is that most every image that crosses your path has been put there for a reason. Nothing happens by accident. What you need to ask yourself isn’t so much Is it true, but Who wants me to believe it—and why?”

An early New Year’s resolution: I intend to remember this book every day before visiting my usual news sites.

Every day.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed