1

The Polished Heart

For the past several years my mind has worked like one of those Magic Eight Balls from my childhood. When I can’t remember the author or title of a book, or even sometimes the name of a friend, I find that if I am patient the answer floats up out of my mind just as the answer floated up, bobbing and weaving, from inside the Magic Eight Ball.

The Polished Heart

For the past several years my mind has worked like one of those Magic Eight Balls from my childhood. When I can’t remember the author or title of a book, or even sometimes the name of a friend, I find that if I am patient the answer floats up out of my mind just as the answer floated up, bobbing and weaving, from inside the Magic Eight Ball.

When I try to remember events of the summer after my wife died, the Magic Eight ball inside my mind begins to do its work. I remember my youngest son sharing my bed during the week following his mother’s death. I remember parts of the funeral and my two older sons bravely doing the readings at Mass. I remember taking my son Jon Pat to get his driver’s license. I remember breaking my foot walking up my gravel driveway at the Palmer House, our bed and breakfast. I remember driving in the rain to view the headstone for the first time and finding my name misspelled—Jeffery rather than Jeffrey—and though the stone-cutters tried to fix this mistake, I became angry every time I walked up to the cemetery until finally I complained and the company replaced the stone without further ado. Later I wondered whether it wasn’t my sloppy handwriting that had caused the mistake. I remember being in the Palmer House with my sister Becky and hearing a single footfall in the upstairs bedroom where Kris had collapsed and how an hour later Becky asked me if I had heard it and how we both looked at each other as we considered this mystery. I remember the generosity and kindness of the many family members and friends, especially those in the homeschool community, who brought us meals for months, who donated money to our children’s college fund, who babysat Jeremy from time to time, who called to see how I was doing.

Then came the school year and the routine of teaching my home-school students. Routine brought more healing. You don’t lose a woman whom you have loved for twenty-eight years without suffering a horrific wound at her loss. But that year the bleeding wound scabbed over and would someday become a scar.

Sixteen months after my wife’s death, I began seeing other women. Encouraged by friends, I turned to the Internet and the online dating sites it offered.

The first woman, Sally, was a Knoxville teacher at a Catholic high school. We exchanged dozens of emails, talked for hours by phone, and decided to get together in person. I drove over the mountains into Tennessee, met her, and became infatuated. Sally was seventeen years younger, had never married, was pretty and personable, and seemed to like me. We saw each other about every other week for almost four months.

In January I drove to Knoxville to meet her parents. I brought Sally a present—a tiny, antique school desk from the Palmer House. She took the gift and we drove to meet her parents, who were only a few years older than I. The meeting went well, or so I thought, and then I drove her home. We were talking, and then she said, incongruously, “I have a friend who’s a private detective.”

“Well, that’s nice, “ I said.

“She can find lots of information online about people.”

“That’s nice.”

The next day was one of those January Sundays bursting with blue skies and sunshine. I called Sally. Sometimes we had talked for four and five hours by phone, but this was one of our shorter conversations.

“I don’t want to see you anymore,” she said.

I was too blind-sided to respond.

“Don’t call me anymore.”

“What’s happened?”

“I’ve changed my mind.”

“But I gave you the desk,” I said stupidly. “I met your parents.”

“You want the desk back, don’t you?”

“What? No. You keep the desk. Only—”

“Goodbye,” she said and hung up.

Why Sally dumped me this way remains a mystery. Did her parents find the difference in our ages a factor? Did her private detective have some information on me? Did she know about my debts, unaware that I would soon sell the house and walk away debt-free?

I have no idea, but I confess I never quite forgave her for the desk.

The next six years brought me into contact with a score of different women from the Internet. With some we took one glance at each other and knew it was over before it had begun. One woman met me at a restaurant in Biltmore Village here in Asheville and within twenty minutes invited me to her home. In another twenty minutes, she had kissed me. That was our first and last date. I am a long-distance runner, and she was a sprinter.

Then there were all the others. A woman named Marjorie loved her home, gardening, and cooking, and was as kind as any woman I ever met, but she was looking for a “soul-mate.” After a year of seeing each other, we decided soul-mates didn’t fit our description. There was the woman I had never met who insisted on driving up from Charlotte when she found I was free one Saturday. She arrived at a place near my apartment, sprang out of her pick-up, and bounded toward me in sweat clothes and with her wind-blown hair revealing a large bald patch on the side of her skull. I played the gentleman, taking her to supper and listening to her describe in detail the work and habits of her deceased husband. There was a woman with autoimmune disease whom I never met, again a widow, who lived near Atlanta, who adored my poetry and who I adored in turn, but we could never really connect except online. Another woman I saw worked for match.com. Her job was to take information, mostly from men who couldn’t write well, and turn their biographies into poetry. She fashioned a sort of living out of this ghostwriting, which both astounded me and roused my admiration. She was very quiet throughout our date, and I tried to make up for her silence by talking. The next day she changed her profile, writing that she preferred to date men who could accept silence and be quiet.

The woman who made the deepest impression on me carried laughter with her wherever she went. She was a bit of a nut, and a bit of trouble, and she could light up a café or even a grocery store with her smile. She talked to anyone, and she listened, and when she did, that other person became entranced. She reminded me of the woman in Theodore Roethke’s “I knew a woman, lovely in her bones.” If you want to know her, read Roethke’s poem. It’s online.

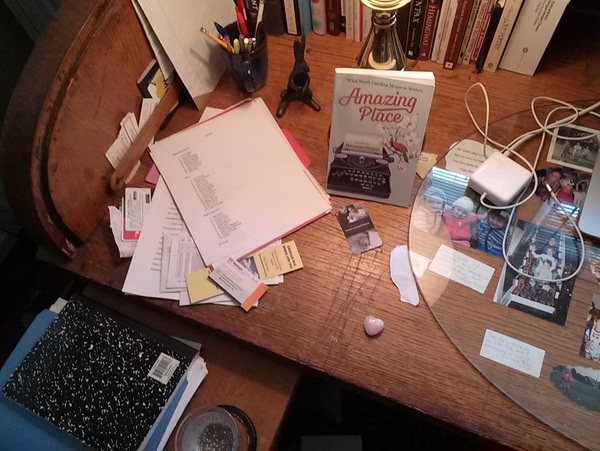

She’s the one who gave me the polished stone heart that sits on my desk amid thesauri and dictionaries, glasses and pens, books and notebooks. Touching that tiny heart reminds me of her and of love with all its joys and sorrows, its highs and lows, its expectations and disappointments, its deep commitments and its frivolity.

Shakespeare once wrote:

“If thou remember'st not the slightest folly

That ever love did make thee run into,

Thou hast not loved.”

By that definition, I am a fool. But I have loved.

Then came the school year and the routine of teaching my home-school students. Routine brought more healing. You don’t lose a woman whom you have loved for twenty-eight years without suffering a horrific wound at her loss. But that year the bleeding wound scabbed over and would someday become a scar.

Sixteen months after my wife’s death, I began seeing other women. Encouraged by friends, I turned to the Internet and the online dating sites it offered.

The first woman, Sally, was a Knoxville teacher at a Catholic high school. We exchanged dozens of emails, talked for hours by phone, and decided to get together in person. I drove over the mountains into Tennessee, met her, and became infatuated. Sally was seventeen years younger, had never married, was pretty and personable, and seemed to like me. We saw each other about every other week for almost four months.

In January I drove to Knoxville to meet her parents. I brought Sally a present—a tiny, antique school desk from the Palmer House. She took the gift and we drove to meet her parents, who were only a few years older than I. The meeting went well, or so I thought, and then I drove her home. We were talking, and then she said, incongruously, “I have a friend who’s a private detective.”

“Well, that’s nice, “ I said.

“She can find lots of information online about people.”

“That’s nice.”

The next day was one of those January Sundays bursting with blue skies and sunshine. I called Sally. Sometimes we had talked for four and five hours by phone, but this was one of our shorter conversations.

“I don’t want to see you anymore,” she said.

I was too blind-sided to respond.

“Don’t call me anymore.”

“What’s happened?”

“I’ve changed my mind.”

“But I gave you the desk,” I said stupidly. “I met your parents.”

“You want the desk back, don’t you?”

“What? No. You keep the desk. Only—”

“Goodbye,” she said and hung up.

Why Sally dumped me this way remains a mystery. Did her parents find the difference in our ages a factor? Did her private detective have some information on me? Did she know about my debts, unaware that I would soon sell the house and walk away debt-free?

I have no idea, but I confess I never quite forgave her for the desk.

The next six years brought me into contact with a score of different women from the Internet. With some we took one glance at each other and knew it was over before it had begun. One woman met me at a restaurant in Biltmore Village here in Asheville and within twenty minutes invited me to her home. In another twenty minutes, she had kissed me. That was our first and last date. I am a long-distance runner, and she was a sprinter.

Then there were all the others. A woman named Marjorie loved her home, gardening, and cooking, and was as kind as any woman I ever met, but she was looking for a “soul-mate.” After a year of seeing each other, we decided soul-mates didn’t fit our description. There was the woman I had never met who insisted on driving up from Charlotte when she found I was free one Saturday. She arrived at a place near my apartment, sprang out of her pick-up, and bounded toward me in sweat clothes and with her wind-blown hair revealing a large bald patch on the side of her skull. I played the gentleman, taking her to supper and listening to her describe in detail the work and habits of her deceased husband. There was a woman with autoimmune disease whom I never met, again a widow, who lived near Atlanta, who adored my poetry and who I adored in turn, but we could never really connect except online. Another woman I saw worked for match.com. Her job was to take information, mostly from men who couldn’t write well, and turn their biographies into poetry. She fashioned a sort of living out of this ghostwriting, which both astounded me and roused my admiration. She was very quiet throughout our date, and I tried to make up for her silence by talking. The next day she changed her profile, writing that she preferred to date men who could accept silence and be quiet.

The woman who made the deepest impression on me carried laughter with her wherever she went. She was a bit of a nut, and a bit of trouble, and she could light up a café or even a grocery store with her smile. She talked to anyone, and she listened, and when she did, that other person became entranced. She reminded me of the woman in Theodore Roethke’s “I knew a woman, lovely in her bones.” If you want to know her, read Roethke’s poem. It’s online.

She’s the one who gave me the polished stone heart that sits on my desk amid thesauri and dictionaries, glasses and pens, books and notebooks. Touching that tiny heart reminds me of her and of love with all its joys and sorrows, its highs and lows, its expectations and disappointments, its deep commitments and its frivolity.

Shakespeare once wrote:

“If thou remember'st not the slightest folly

That ever love did make thee run into,

Thou hast not loved.”

By that definition, I am a fool. But I have loved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed