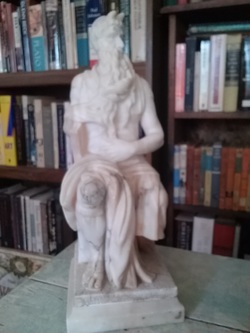

On the small green table of my living room sits a reproduction of Michelangelo’s Moses. This statue, precisely one foot high, is my most recent acquisition, given me by my father shortly before he died this past April.

Foolishly, I never asked my father why he owned the statue or what had possessed him to purchase it, and now, of course, the time has passed for such questions.

Various critics have disagreed in their interpretations of “Moses.” Scholars debate one another about the meaning of the horns on the statue’s head, the symbolism of his fingers touching the beard and hair, and the fierce expression on his face.

In a sense, the statue represents my father. He was also a hard man to figure out. We’ll be coming back to him from time to time in Wolves In The Attic, but for now I will focus on his life, putting together here a brief outline of his years as I understand them, much as an archaeologist might assemble shards of pottery into a vase.

Foolishly, I never asked my father why he owned the statue or what had possessed him to purchase it, and now, of course, the time has passed for such questions.

Various critics have disagreed in their interpretations of “Moses.” Scholars debate one another about the meaning of the horns on the statue’s head, the symbolism of his fingers touching the beard and hair, and the fierce expression on his face.

In a sense, the statue represents my father. He was also a hard man to figure out. We’ll be coming back to him from time to time in Wolves In The Attic, but for now I will focus on his life, putting together here a brief outline of his years as I understand them, much as an archaeologist might assemble shards of pottery into a vase.

My father was born in 1925. He came of age in Pennsylvania during the Depression, when for a time his family was poor as dirt. Once my grandfather deserted the family for a year, traveling to California ostensibly to look for work and leaving my grandmother to provide for her two sons. When he returned, Grandpa found work in an ice cream factory. Because they lacked a refrigerator, Grandpa would wake his sons when he returned at three o’clock in the morning to eat the ice cream he had brought from the factory. For a time, too, I think, they lived in a building in Western Pennsylvania with only an earthen floor. Once at a family gathering my uncle happened to say “We were poor back then,” and my grandmother, a proud woman of Scots-Irish descent, turned on him in horror and fury: “We were never poor!” Later Grandpa turned to carpentry and building, making better money and leaving New Castle with several well-constructed homes.

As a teenager, Dad earned the rank of Eagle Scout and joined the cheerleading squad at Neshannock High School in New Castle. (My dad the cheerleader lacks the punch of my dad the halfback, but this was Pennsylvania and they grow big boys up there.) After graduation he attended Penn State for a year, studying to be a forester until the draft pulled him into the Army and World War II. He spent the next two years training in Texas and then fighting Germans in Italy’s Po River Valley. Sometimes when I was a boy he told me stories of those days. Once, for instance, he and a superior were entering the basement of an Italian house, checking for German soldiers. The other man insisted on entering first, and a mine beneath one of the steps blew his foot away. Another time Dad and his men—he was by then a squad leader—captured several German officers eating supper at a long table in an another Italian house. When the war in Europe ended, my father and others were preparing to invade Japan when the atomic bomb ended that necessity.

After the war, Dad attended Westminster College in Pennsylvania, married my mother, and inspired by his brother, who had earned his M.D., entered Temple University Medical School and Hospital, where I was later born.

Dad completed his internship in Johnstown, Pa., renowned for its famous flood, and then accepted an offer to open practice in Boonville, North Carolina. There, as the only general practitioner in town, he lived an extremely busy life, tending to his patients and delivering more than six hundred babies. (I those days small town family practitioners often doubled up as obstetricians and general surgeons.) He was active in the Methodist Church and the Lions’ Club, and took up painting, which became a lifelong hobby. He also ended the practice of separate waiting rooms for black and white patients, striking a tiny blow in 1956 for civil rights. My grandfather built the house in which we lived, a house owned today by my sister.

Then came the “greener pastures decades”, the moves and changes that shook up our family and my father’s professional life. He took our family first to nearby Winston-Salem, where he worked for the Reynolds Tobacco Company for a year. Dissatisfied with that position, he opened a private practice, eventually welcoming his brother into the practice, a decision that ended in a tangle of hard feelings lasting several years. He moved next to Florida, where he divorced my mother. With his new wife, he then bought a farm in Traveller’s Rest, South Carolina, and set up another practice. Finally, he and Kay traveled back to Florida, where he ended his career working in a state prison as their physician.

My relationship with this man was complicated.

Until he was in his eighties, for instance, Dad was short on compliments toward his children. I remember his criticisms both as a child and an adult, but compliments were rare. An example: when I told him in my senior year of high school that I intended to apply to West Point, a dream of mine since elementary school, he replied, “I hope you know your chances for getting in are slim.” My subsequent letter of admission astounded him. Another example: at the age of forty-one, I joined the Roman Catholic Church. That Sunday after Mass I called him to share this good news: “Dad, I just wanted to tell you that today I became a Catholic.” He paused, then said: “You know I’ve always had a problem with the Catholic Church because of its stance on birth control.” For once in my life a retort dropped readily from my tongue: “Dad, you had six children with Mom. Which ones did you want to get rid of?”

My dad gave some gifts to the world. Both he and his brother illustrate the idea of the American Dream, pulling themselves by force of will out of poverty to become physicians. Dad taught his children the value of hard work. He provided for his family. Many of his patients adored him. He delighted in the world of nature—he knew the names of birds, flowers, and trees, and while eating he often kept up a running commentary about the visitors to the bird feeder outside his dining room window. He overindulged his dogs and cats. On every home in which he lived he made his mark, most often by building a rock wall. As I said, he painted, leaving behind some nice landscapes, and he even dabbled in writing, self-publishing a novel and putting together some less distinguished poetry.

As for how he treated his friends and family…de mortuis nihil nisi bonum. Let’s just say that for most of his life Dad had difficulty loving those close to him.

Which made him a difficult man to love in return.

As a teenager, Dad earned the rank of Eagle Scout and joined the cheerleading squad at Neshannock High School in New Castle. (My dad the cheerleader lacks the punch of my dad the halfback, but this was Pennsylvania and they grow big boys up there.) After graduation he attended Penn State for a year, studying to be a forester until the draft pulled him into the Army and World War II. He spent the next two years training in Texas and then fighting Germans in Italy’s Po River Valley. Sometimes when I was a boy he told me stories of those days. Once, for instance, he and a superior were entering the basement of an Italian house, checking for German soldiers. The other man insisted on entering first, and a mine beneath one of the steps blew his foot away. Another time Dad and his men—he was by then a squad leader—captured several German officers eating supper at a long table in an another Italian house. When the war in Europe ended, my father and others were preparing to invade Japan when the atomic bomb ended that necessity.

After the war, Dad attended Westminster College in Pennsylvania, married my mother, and inspired by his brother, who had earned his M.D., entered Temple University Medical School and Hospital, where I was later born.

Dad completed his internship in Johnstown, Pa., renowned for its famous flood, and then accepted an offer to open practice in Boonville, North Carolina. There, as the only general practitioner in town, he lived an extremely busy life, tending to his patients and delivering more than six hundred babies. (I those days small town family practitioners often doubled up as obstetricians and general surgeons.) He was active in the Methodist Church and the Lions’ Club, and took up painting, which became a lifelong hobby. He also ended the practice of separate waiting rooms for black and white patients, striking a tiny blow in 1956 for civil rights. My grandfather built the house in which we lived, a house owned today by my sister.

Then came the “greener pastures decades”, the moves and changes that shook up our family and my father’s professional life. He took our family first to nearby Winston-Salem, where he worked for the Reynolds Tobacco Company for a year. Dissatisfied with that position, he opened a private practice, eventually welcoming his brother into the practice, a decision that ended in a tangle of hard feelings lasting several years. He moved next to Florida, where he divorced my mother. With his new wife, he then bought a farm in Traveller’s Rest, South Carolina, and set up another practice. Finally, he and Kay traveled back to Florida, where he ended his career working in a state prison as their physician.

My relationship with this man was complicated.

Until he was in his eighties, for instance, Dad was short on compliments toward his children. I remember his criticisms both as a child and an adult, but compliments were rare. An example: when I told him in my senior year of high school that I intended to apply to West Point, a dream of mine since elementary school, he replied, “I hope you know your chances for getting in are slim.” My subsequent letter of admission astounded him. Another example: at the age of forty-one, I joined the Roman Catholic Church. That Sunday after Mass I called him to share this good news: “Dad, I just wanted to tell you that today I became a Catholic.” He paused, then said: “You know I’ve always had a problem with the Catholic Church because of its stance on birth control.” For once in my life a retort dropped readily from my tongue: “Dad, you had six children with Mom. Which ones did you want to get rid of?”

My dad gave some gifts to the world. Both he and his brother illustrate the idea of the American Dream, pulling themselves by force of will out of poverty to become physicians. Dad taught his children the value of hard work. He provided for his family. Many of his patients adored him. He delighted in the world of nature—he knew the names of birds, flowers, and trees, and while eating he often kept up a running commentary about the visitors to the bird feeder outside his dining room window. He overindulged his dogs and cats. On every home in which he lived he made his mark, most often by building a rock wall. As I said, he painted, leaving behind some nice landscapes, and he even dabbled in writing, self-publishing a novel and putting together some less distinguished poetry.

As for how he treated his friends and family…de mortuis nihil nisi bonum. Let’s just say that for most of his life Dad had difficulty loving those close to him.

Which made him a difficult man to love in return.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed