If Mrs. Gosp was our guest Venusian, then Mrs. Irene Harrison was our time traveller.

When Mrs. Harrison first came to stay at the Palmer House for a few days in the mid-1990s, she was 104 years old. She was a little sparrow of a woman, barely five feet tall, who arrived by car with her son. She had come to Waynesville to receive vitamin and natural health treatments for her cataracts from a local physician specializing in such an approach. I don’t know why she chose this route instead of lazar surgery, which is quick and safe, except to say that Mrs. Harrison was a strong believer in a healthy diet and natural ways. She returned to the Palmer House on at least two other occasions following this visit, renting the large, sunny room with the queen-sized bed on the second floor. Her son—and later her daughter—stayed in the room opposite.

When Mrs. Harrison first came to stay at the Palmer House for a few days in the mid-1990s, she was 104 years old. She was a little sparrow of a woman, barely five feet tall, who arrived by car with her son. She had come to Waynesville to receive vitamin and natural health treatments for her cataracts from a local physician specializing in such an approach. I don’t know why she chose this route instead of lazar surgery, which is quick and safe, except to say that Mrs. Harrison was a strong believer in a healthy diet and natural ways. She returned to the Palmer House on at least two other occasions following this visit, renting the large, sunny room with the queen-sized bed on the second floor. Her son—and later her daughter—stayed in the room opposite.

Mrs. Harrison often wore a mix of colors and fabrics that made me think of some tiny Czech doll. Usually, she was very well put-together, displaying a grace and dignity indicative of her upbringing. Only once, early one morning as she was crossing the hall to her son’s room, did I see her unkempt. She hadn’t taken the time yet to put herself together from her night’s sleep, and her hair stuck up from her head, her eyes were slightly askew, with one looking as if it might pop from its socket, and she was laboring slowly and stiffly across the hall. Later she told me she usually required half an hour in bed on waking just to limber up, flexing her arms and legs, fingers and toes.

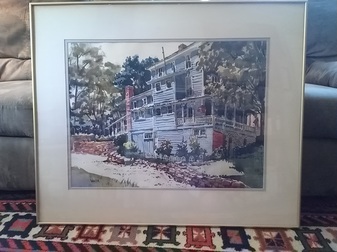

Mrs. Harrison fascinated me for a number of reasons. First, of course, was her age. Think about it. Born in 1890, she had seen a world jump from carriages, gas lights, and bustle dresses to Concorde jets, men on the moon, and miniskirts. The picture shown here is of her at about the age of eighteen.

Then there was her personal history. Mrs. Harrison’s father, F.A. Seiberling, and her uncle were the founders of Goodyear Tire. From the age of eight, when she threw the first switch on the production line, Mrs. Harrison was involved with the company that became a giant in the manufacture of automobile tires. Born near the end of an era when some men—Rockefeller, Morgan, Carnegie, and others—were creating massive fortunes, she and her siblings grew up in a world of privilege. She was in her twenties when her father finished Stan Hywet, a hundred-room mansion on fourteen hundred acres. Later, in 1957, she and others in the family opened this property to the public. Mrs. Harrison later lived in the Gate Lodge of Stan Hywet until her death.

The old axiom—“With great privileges come great responsibilities”—was practiced by the Seiberling family. Mrs. Harrison founded a group that gave birth to the United Way, she marched as a suffragette, and she took a small part in the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous, which held its first meetings in the Gate Lodge when Mrs. Harrison’s sister and her family lived there.

Mrs. Harrison’s most memorable story, however, stemmed from 1912 when her father instructed his twenty-one year old daughter to arrange passage back to America from their European tour. Because of a change in their travel plans, Mrs. Harrison was forced to cancel the berths she had booked on the Titanic.

Once I was walking through the living room where Mrs. Harrison and her son were discussing the dangers of fluoride. Mrs. Harrison was conservative about certain matters and believed fluorides were a plot to rot the brains and bones of the American public. That year, at the age of 104, she was organizing a campaign to convince Akron officials to rid the city’s water supply of its fluoride.

After collecting the mail from the box on the front porch, I stopped at the edge of the room and said, “Mrs. Harrison, you’ve lived a long life. Who was your favorite president?”

“Roosevelt,” she answered. She had this piping voice when she was excited that always made me smile.

“Roosevelt?” I repeated, taken aback. That choice seemed odd for a conservative. FDR had helped usher in the welfare state and big government.

“Theodore Roosevelt,” Mrs. Harrison said, in that piping voice. “We’ve had no one like him since. All that energy, all that drive, and brave in the bargain.”

One morning, when I was asking her at breakfast about her life, Mrs. Harrison invited me to sit at her table for a few minutes.

“Let me tell you at story,” she said. “It will show you how things were then.

“There was a time when my father’s company was in trouble with a bank. The company was struggling and the bank was getting ready to collect the note, which would have meant bankruptcy for my father. He was more an inventor than a businessman, and every time my husband, who was also a banker, tried to talk to him about money, my father would wave him away. ‘Something will turn up,’ he’d say.

“Now in those days my husband used to meet a classmate from college in Manhattan once a year. They’d spend three days going to different Broadway shows and catching up with each other. On this particular occasion his friend had spent the past year doing business in Mexico.

“That first night when they met for supper, this friend asked my husband, ‘So how’s your father-in-law doing?’

“My husband explained the financial situation, that my father was on the verge of bankruptcy and all he wanted to do about it was go on tinkering with his tires at the plant.

“Well, that friend just smiled and took out his check book and wrote a note for several hundred thousand dollars, which he passed to my husband. ‘I had some luck with oil in Mexico,’ he said. ‘Tell him to pay me back when he can. I know he’s good for it.’

“So my husband comes home the next week and shows the check to my father. ‘He’s a good man,’ my father said. ‘We’ll send the check by messenger to the bank tomorrow.’

“My husband couldn’t get over my father’s nonchalance. ‘I’m taking it myself,’ he said, and the next day he marched into that bank and plopped that check down on the manager’s desk.”

A good story. And as for energy, drive, and bravery, Mrs. Harrison had them in spades.

Mrs. Harrison fascinated me for a number of reasons. First, of course, was her age. Think about it. Born in 1890, she had seen a world jump from carriages, gas lights, and bustle dresses to Concorde jets, men on the moon, and miniskirts. The picture shown here is of her at about the age of eighteen.

Then there was her personal history. Mrs. Harrison’s father, F.A. Seiberling, and her uncle were the founders of Goodyear Tire. From the age of eight, when she threw the first switch on the production line, Mrs. Harrison was involved with the company that became a giant in the manufacture of automobile tires. Born near the end of an era when some men—Rockefeller, Morgan, Carnegie, and others—were creating massive fortunes, she and her siblings grew up in a world of privilege. She was in her twenties when her father finished Stan Hywet, a hundred-room mansion on fourteen hundred acres. Later, in 1957, she and others in the family opened this property to the public. Mrs. Harrison later lived in the Gate Lodge of Stan Hywet until her death.

The old axiom—“With great privileges come great responsibilities”—was practiced by the Seiberling family. Mrs. Harrison founded a group that gave birth to the United Way, she marched as a suffragette, and she took a small part in the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous, which held its first meetings in the Gate Lodge when Mrs. Harrison’s sister and her family lived there.

Mrs. Harrison’s most memorable story, however, stemmed from 1912 when her father instructed his twenty-one year old daughter to arrange passage back to America from their European tour. Because of a change in their travel plans, Mrs. Harrison was forced to cancel the berths she had booked on the Titanic.

Once I was walking through the living room where Mrs. Harrison and her son were discussing the dangers of fluoride. Mrs. Harrison was conservative about certain matters and believed fluorides were a plot to rot the brains and bones of the American public. That year, at the age of 104, she was organizing a campaign to convince Akron officials to rid the city’s water supply of its fluoride.

After collecting the mail from the box on the front porch, I stopped at the edge of the room and said, “Mrs. Harrison, you’ve lived a long life. Who was your favorite president?”

“Roosevelt,” she answered. She had this piping voice when she was excited that always made me smile.

“Roosevelt?” I repeated, taken aback. That choice seemed odd for a conservative. FDR had helped usher in the welfare state and big government.

“Theodore Roosevelt,” Mrs. Harrison said, in that piping voice. “We’ve had no one like him since. All that energy, all that drive, and brave in the bargain.”

One morning, when I was asking her at breakfast about her life, Mrs. Harrison invited me to sit at her table for a few minutes.

“Let me tell you at story,” she said. “It will show you how things were then.

“There was a time when my father’s company was in trouble with a bank. The company was struggling and the bank was getting ready to collect the note, which would have meant bankruptcy for my father. He was more an inventor than a businessman, and every time my husband, who was also a banker, tried to talk to him about money, my father would wave him away. ‘Something will turn up,’ he’d say.

“Now in those days my husband used to meet a classmate from college in Manhattan once a year. They’d spend three days going to different Broadway shows and catching up with each other. On this particular occasion his friend had spent the past year doing business in Mexico.

“That first night when they met for supper, this friend asked my husband, ‘So how’s your father-in-law doing?’

“My husband explained the financial situation, that my father was on the verge of bankruptcy and all he wanted to do about it was go on tinkering with his tires at the plant.

“Well, that friend just smiled and took out his check book and wrote a note for several hundred thousand dollars, which he passed to my husband. ‘I had some luck with oil in Mexico,’ he said. ‘Tell him to pay me back when he can. I know he’s good for it.’

“So my husband comes home the next week and shows the check to my father. ‘He’s a good man,’ my father said. ‘We’ll send the check by messenger to the bank tomorrow.’

“My husband couldn’t get over my father’s nonchalance. ‘I’m taking it myself,’ he said, and the next day he marched into that bank and plopped that check down on the manager’s desk.”

A good story. And as for energy, drive, and bravery, Mrs. Harrison had them in spades.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed